|

While the construction industries stakeholders are worried about payment, the legal fraternity is rather worried about the nuances of how to “stay” and how to seek “leave” of the Adjudication Decisions (‘AD’) in court.

A ‘stay’ for an Adjudication Decision (AD), is commonly known as a suspension for the AD to be enforced, under s.16 CIPAA, pending ‘setting aside’ by the court or final determination by the court or in arbitration. Whereas, ‘enforcement’ comes under s.28 CIPAA, the other end of the matrix. Thus the question, whether an AD, after having been enforced as an Order of the Court, can be stayed, and if so, would the Federal Court decision in View Esteem Sdn Bhd v Bina Puri Holdings Sdn Bhd [2018][1] be overruled? Such is the “leave” questions to the Federal Court in ASM Development (KL) Sdn Bhd v Econpile (M) Sdn Bhd Anor [2023][2]. Follows up, in the series of cases[3], the court will inclined to dismiss the stay when there is no clear or unequivocal error in the AD; even if there is an ongoing arbitration or litigation; and when there is no real risks of the inability to repay the adjudicated sum. However, as in another situation[4], a conditional stay maybe granted if court finds there is real risks of the inability to repay the adjudicated sum. In summary, unless otherwise there is a gross injustice, the court tends to dismiss the stay when the AD has been upheld earlier. ------------------------------------------- [1] MLJ 22; [2019] 5 CLJ 479 [2] 4 MLJ 720 [3] Ahmad Zaki v Versalink Marketing [2023] CLJU 1193; AMD Construction and Engr v LDE Projects Anor [2023] CLJU 1651; Wabina Constructions v LDE Projects Anor [2023] CLJU 1651; BMG Global v Juang-Antara Bina [2023] CLJU 2407; Meridian Contracts v Baeur (Malaysia) Anor [2023] MLJU 3043; Classic Series v Ng Lung Yang [2023] CLJU 2066 and Land Success Engineering v Amindo Packaging Anor [2023] MLJU 3146: no arbitration commence. [4] Mudajaya Corporation Bhd v KWSL Builders Sdn Bhd & Anor [2023] 6 CLJ 770; Samsung C&T Corp UEM Construction JV Sdn Bhd v Eversendai Constructions (M) Sdn Bhd [2023] CLJU 2319

0 Comments

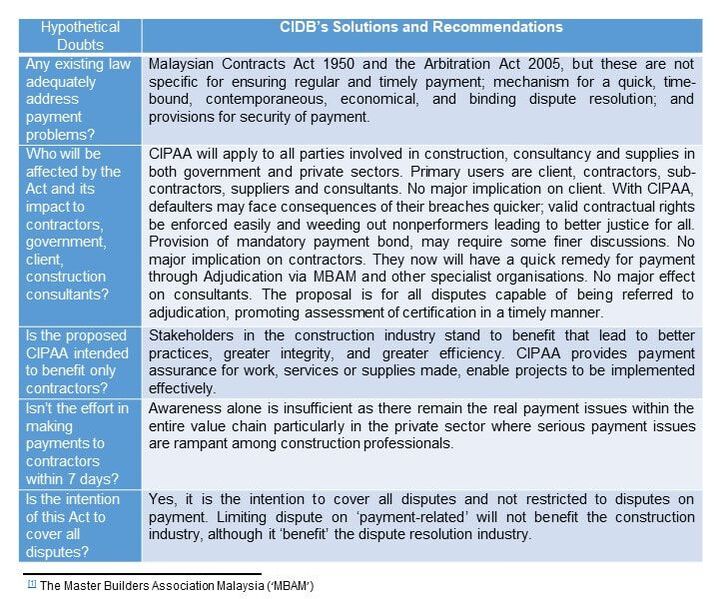

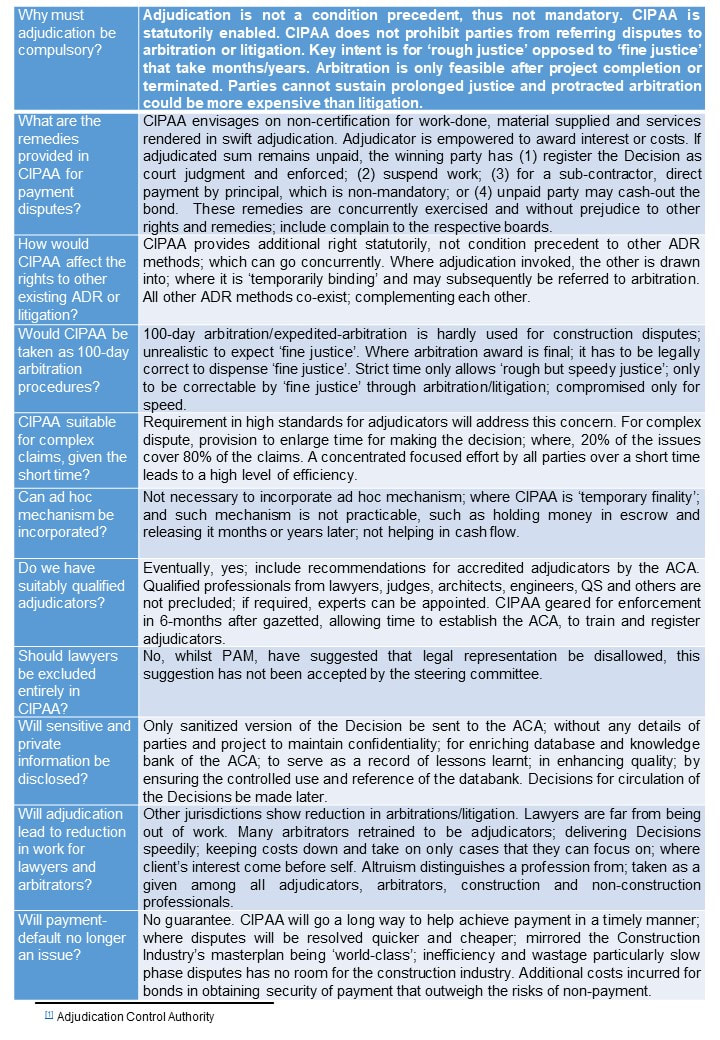

AbstractThis article aims at investigating the inception; growth; and recent development of the role of adjudication in the Malaysian construction industry, from a perspective of an adjudicator. It commences with the issue, whether the creation of the Construction Court and Construction Industry Payment Adjudication Act 2012 (‘CIPAA’) resolved the construction industry’s conundrum? Looking at its inception phase, the industrial stakeholders with Construction Industry Development Board (‘CIDB’) as the forerunner since 2003, has championed the course, only to be ‘derailed’ by the Bar Council (‘BC’) with its ‘hypothetical doubts’ as to the viability of the CIBD’s version of CIPAA. Together with the AIAC, the BC lobbied the AC’s Chamber to implement the AIAC’s version of the CIPAA legislation, leaving a ‘bitter after-taste’ to the CIDB’s earlier efforts, now begging the question, how CIPAA fares in its growth stage? Next, pondering at the astronomical growth of CIPAA with 89% success rate, 4-years into implementation of CIPAA, it has since evolved into ‘mini trials’, ‘document only arbitration’ or even ‘fast track or expedited arbitration’. In a nutshell, the findings of View Esteem Sdn Bhd v Bina Puri Holdings Sdn Bhd[1] hereinafter (‘View Esteem’), reverses a body of jurisprudence developed in those 4 years making CIPAA complicated, inefficient and lost its focus. This follow by the peeling into the current state of the CIPAA, to draw upon the correct definition of the problem such as complication; monopoly; and over legalistic, generating the ‘push effect’ for the construction stakeholders away from CIPAA. Notwithstanding the pro-adjudication approach taken by the court. Hoping for solutions that will almost surface within, in the turbulence of the ‘ocean of legal-entanglement’, stakeholders are forced to look back to the ‘star’ for guidance and to salvage the ‘compass’ that had been so conveniently casted away, to guide the CIPAA vessel to its next destination of glory if any, in the following area of structural, procedural and institutional reform, begging the question, what can really be done? ------------------------------------------------------------ [1] [2019] 5 CLJ 479; [2017] 1 LNS 1378. Introduction Abraham observed that backlog of construction dispute to be resolved by the Malaysian courts were staggering snail-paced and costly albeit the lacked of official statistic.[1] As reported by Balogun, over 300,000 construction disputes are pending in courts (2006-2008).[2] This alarming situation as argued by Varghese, is similar to India.[3] The World Bank went as far as to find a solution to mitigate this.[4] One way, as suggested by CIDB[5] is ‘to emulate TCC courts[6] of the UK’[7], by having Malaysian’s own Construction Courts and such was materialised in 2014, 2-years after CIPAA[8] was conceived to resolve construction dispute, in a rough justice manner.[9] However, does the creation of the Construction Court and CIPAA resolved the construction industry’s conundrum? The Inception In reality, NO. According to CIDB, before the conceived idea of statutory adjudication, as promoted by Lim, has been ‘pursued by the Asian International Arbitration Centre (‘AIAC’)’[10] in the form of CIPAA,[11] there were ‘fears’ casted upon by the Bar Council (‘BC’), as argued by Ali, inevitably forced CIDB to provide for solutions to these 19-questions[12] hereinafter, (‘hypothetical doubts’), pointing to BC, being not a party to the steering committee at that time[13], and such one may presume as to why such doubts had been casted. In attempt to pursue such undertakings by the CIDB, as early as 2003[14], Ali argued that such doubts, which were hypothetical, can be overcome as the positive effects of CIDB’s version of CIPAA to the construction industry, override these ‘hypothetical doubts’[15] that Lam finds them ‘unsuitable for a number of reasons’[16]. Lam further argued, the CIDB’s draft included ‘a definition of construction contract of a dispute which could have had the effect of having a hillside collapse like Highland Towers being referred to the Adjudicator for a decision in a matter of weeks’; also ‘subjecting the individual house owner to an adjudication process, ignoring that it is the house owner who generally complains’; and most importantly, ‘CIDB is in control of registering and appointing adjudicators’.[17] How true were these doubts? Critically, Lam pointed, under the aegis of the AG’s[18] chamber and together with the AIAC, the improved formulation of CIPAA was materialised in 2012, enforced in 2014[19] and the rest, were said to be history, leaving a ‘bitter after-taste’ to the CIDB’s earlier efforts since 2003.[20] At this juncture, in responding to Lam’s observation and many others in the BC, Ali and Sr. Lim Chong Fong [as he was known then, now a HC Judge] via the CIDB ‘took the bull by the horns’, by providing the solutions, condensed from the 19 to these, as the followings[21]: --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- [1] Zhen, ‘A specialised Construction Court, finally?’, (4 Mar 2013), <https://www.malaysianbar.org.my/article/news/legal-and-general-news/legal-news/a-specialised-construction-court-finally>, accessed 16 Feb 2022. [2] Balogun and others, ‘Adjudication and arbitration as a technique in resolving construction industry disputes: A literature review’, (2017), ACSEE. [3] Varghese, ‘Transforming India as a Centre for International Arbitration: Recommendation for Reforming the Arbitration Law of India’ (LLM, RGU, 2018), p11. [4] World Bank, ‘Malaysia: Court Backlog and Delay Reduction Program, A Progress Report’, (Aug 2011), <https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/16791/632630Malaysia0Court0Backlog.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y>, accessed 16 Feb 2022. [5] Construction Industry Development Board (‘CIDB’). [6] The Technology and Construction Court (“TCC”) is a specialist court, which deals principally with technology and construction disputes. [7] Technology and Construction Court, <https://www.gov.uk/courts-tribunals/technology-and-construction-court>, accessed 16 Feb 2022. [8] Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act 2012 (‘CIPAA’). [9] Edge Prop, ‘First two Construction Courts Launched’, (15 Apr 2014), <https://www.edgeprop.my/content/first-two-construction-courts-launched>, accessed 16 Feb 2022. [10] Balogun [n 4]: citing Ali, ‘CIPAA: Reducing Payment-Default and Increasing Dispute Resolution Efficiency in Construction’, (2006), CIDB-WG10. [11] Lim and others, ‘Adjudication of Construction Dispute in Malaysia’, (Lexis Nexis, 2014) [12] Ali and Lim, ‘A Report on the Proposal for A Malaysian Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act: CIPAA’ (Dec 2008), CIDB, p.14-23. [13] Ali [n14], p.12. [14] Ali [n14], p.4-5. [15] Ali, ‘A Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act: Reducing Payment-Default and Increasing Dispute Resolution Efficiency in Construction’ (2006) MBAM Journal, part 1 and 2, p.4-22. [16] Lam and Loo, ‘The Statutory Framework and Features of the CIPAA Act 2012’ (2018 Sweet and Maxwell), P.13, [1.036]. [17] Lam [n18], p.13. [18] Attorney General (‘AG’) [19] CIPAA 2012, s.1(2); Federal Government Gazette PU(B)124, 14 Apr 2014. [20] Lam [n18], p.13. [21] Ali [n17], p.4-22. Since 2014, there has been an astronomical increase in CIPAA adjudications related feedstock of cases in courts[1], as compare to the other forms of ADR[2], surpassing even arbitration. It now begs the question, how CIPAA fares in its growth stage?

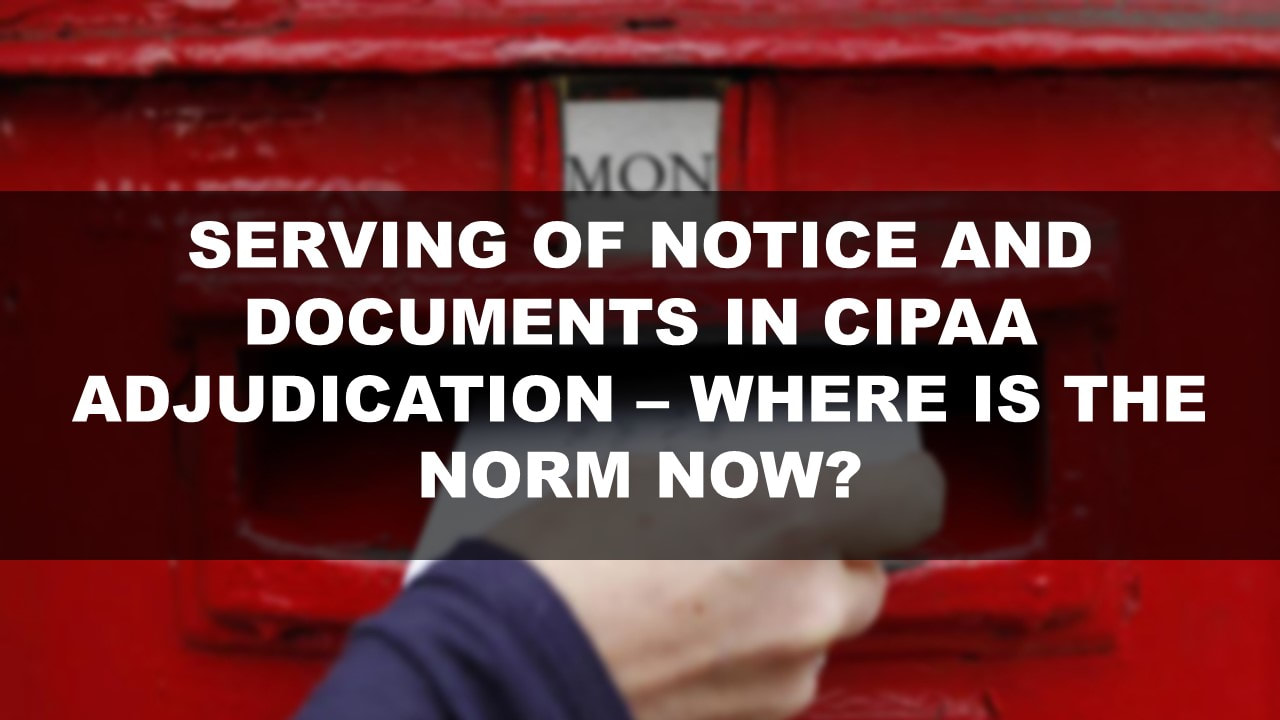

The Growth AIAC (2016) statistic showed, CIPAA has since grown to be an extremely successful for Claimant to retrieve its unpaid sum with 89% success rate.[3] Such landmark success rate eventually turning the acronym ‘CIPAA’ into a verb such as, ‘I will CIPAA you’. It has come a point, as rightly observed by Chan, ‘one may even be discouraged upon receiving the Payment Claim’ to even serve its Response.[4] What if a party refuse to participate? What are the consequences of failing to participate in an adjudication?[5] Simple as these questions maybe, in Chan’s observation, it is potentially a ‘trap’ for setting aside under s.15 of CIPAA for a ‘novice adjudicator’.[6] Setting aside appears to be the norm lately, although within a narrow ambit. The early case law as in Wong Huat Construction v Ireka Engineering & Construction[7], it was held that ‘setting aside’ restores all parties to their original positions and parties are free to adjudicate, shortfall of foreseeing complication whether can a Decision be severed, as to only enforce the enforceable part? Naza Engineering v SSL Dev[8], held that court has no power to set aside a part of the Decision, relying on BM City v Merger Insight[9]. Finding in contrast in JEKS Engineering v PALI PTP[10], the court has power to severe any part of the Decision. What is taken to be settled are, one, court could not set aside Decision on grounds of mistake in facts and/or in law; the court will not re-evaluate the evidence; and any reasons, brief as they may be, is taken as the adjudicator’s justification. Revisiting Chan’s earlier assertion, these traps potentially evolved into ‘guerrilla tactics’[11] as in (1) application to extend time for submission citing not having to receive client’s instruction, failing which, counsel will resign; (2) adjudicator risks breaching natural justice by not allowing parties to ventilate the next course of action, by proceeding ex-parte; and (3) totally ignore CIPAA entirely, to deal later, claiming fraudulent, although such has been given the strictest proof.[12] After 4-years into its success story, the Federal Court’s (‘FC’) decision in View Esteem v Bina Puri Holdings[13] (‘View Esteem’) throw the ‘pendulum of success’ into ‘disarray’, allowing matters raised beyond the Payment Response to be adjudicated.[14] In Foo’s observation, such decision, ‘reverses a body of jurisprudence developed in those 4 years, as well as the general understanding and practice of the industry’.[15] Such findings accentuate, whether the procedures put in place suitable for complex claims, which could revolve around complex questions of fact and law, which is now a reality.[16] Similarly, adjudicators are forced to decide on ‘Final Account’, a subject aptly for litigation or arbitration.[17] In Martego v Arkitek Meor & Chew[18] (‘Martego’), CIPAA applies to matter pertaining to ‘final claims’ where the term ‘progress payment’, as interpreted by the courts, was wide enough to include the ‘final payment’, so long there are payment claims relating to construction contract. The same ought to be said, Payment Claim are revisable and it does not bound by the amount set out in the Payment Claim.[19] Apparently, courts would not have understood the concerns, ‘given the short time period within which to handle a claim, is the possibility of unjust, incorrect and aberrant decisions real?’[20] Both CIDB and the AIAC only contemplated, ‘interim payment issues’ not ‘final account’, but findings in Martego accentuated Lam’s concern, ‘the effect of having a hillside collapse like Highland Towers being referred to the Adjudicator for a decision in a matter of weeks’.[21] Also, ‘it has been suggested by PAM[22], but was not accepted that lawyers would not be allowed to act as adjudicators or represents parties to disputes referred to adjudication’.[23] As Harban observed, with involvement of lawyers, CIPAA has evolved into ‘something else’ being ‘complicated and overly legalistic’. Harban pointed out, ‘CIPAA was meant to assist lay persons so that they can be self-represented nevertheless, this has been complicated with the direct involvement of legal practitioners’[24], eventually led to various complications that in Foo argued, ‘reverses a body of jurisprudence developed in those 4 years, as well as the general understanding and practice of the industry’.[25] As apparent, these ‘legal charade’, dressed up as the questions of law, i.e. Retrospective versus prospective[26]; Non-certified payment[27]; Winding up conundrum[28]; Singular versus Multiple Contract[29] and of many more others[30]. Common procedural matter such as ‘notice deemed served’, became an unsettled affairs, i.e. proof of mailing is not the proof of receiving following Yap Ke Huat v Pembangunan Warisan Murni Sejahtera[31], notice cannot be deemed served with AR-Registered, also in Goh Teng Whoo v Ample Objectives[32], AR-Registered does not conclusively mean, the recipient has received the same. AR-Registered continues to be interpreted as service are ‘presumed’, until the contrary is proven.[33] These are legal complexities that baffled lay ‘technical adjudicator’. CIDB initially has a wider view to include ‘all disputes and not just restricted to disputes related to payment issues’[34]. Lam argued, by such, CIDB’s proposal will include ‘subjecting the individual house owner to an adjudication process, ignoring that it is the house owner who generally complains’.[35] This subsequently, led to the dilemma for PAM, as contained within its Standard Form of Building Contract (‘SFBC’), a provision for ‘contractual adjudication’[36] which initially a multi-tier arbitration clause which Rajoo pointed, is a misnomer against statutory mandated adjudication, CIPAA.[37] Such conundrum potentially left a lacuna, as in s.3 of CIPAA: Non-Application, whether such cl.36 of PAM SFBC 2018 will also be construed as ‘contracting out’ of CIPAA, based on the doctrine of ‘free to contract’? In Ranhill E&C Sdn Bhd v Tioxide (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd[38], it was held that the terms of CIPAA as a legislation prohibits the parties from contracting out of its application, notwithstanding that there is no express term within the Act. Any forms of contractual arrangement for dispute resolution would not exclude the application of CIPAA. Thus, the issues in relation with s.3 of CIPAA: Non-Application, has no other avenue for recourse, beside arbitration and litigation. The current state of CIPAA being compulsory, in essence, deviated from the original intend of CIDB when it attempts to address, ‘if parties decide not to opt to exercise their rights to adjudication, they may opt for other dispute resolution’, to include adjudication by contract.[39] Further, non-application of CIPAA, eventually led to ‘split-hair’ arguments as to whether, ‘lost and expense’ (‘L&E’); ‘liquidated damages’ (‘LD’); and ‘extension of time’ (‘EOT’), fall within the jurisdiction of CIPAA? These issues are not entirely payment issues, per se. In Syarikat Bina Darul Aman v Government of Malaysia[40], it was held that adjudicator must decide on L&E claims as such claims came within the ambit of CIPAA. These claims were due to the delay in completion of works and therefore payable as part of the amount claimable for the additional costs incurred for work. However, not all L&E claims are within the purview of CIPAA, i.e. claim for special damages. Then again, this matter is truly unsettled, if the L&E is not a provision of the contract, it cannot be awarded by the Adjudicator.[41] In another case, the High Court (‘HC’) held L&E is not a ‘payment’, thus not allowable in s.4, CIPAA[42]. In yet, another case, notice requirement is only apply to loss that is ‘beyond reasonably contemplated’.[43] Despite these hypothetical doubts, 4-years into implementation of CIPAA, Harban argued, ‘CIPAA being complicated with the direct involvement of legal practitioners, now lengthened because the decision is subjected to appeal all the way to the FC. Due to the complexity and lengthy processes, smaller industry players are no longer benefiting from the adjudication process; these players are intimidated by the complicated process; making adjudication having little difference compared to litigation or arbitration’.[44] In a nutshell, CIPAA is complicated, inefficient and lost its focus.[45] It has since evolved into ‘mini trials’, ‘document only arbitration’ or even ‘fast track arbitration’, for instance, holding to the principle in View Esteem, Respondent has the right to ‘throw in the kitchen sink’[46] at any point in time during the progress of CIPAA, eventually leading to submission of voluminous ‘expert reports’ and seek for hearings to be held, which in MRCB Builders v Wazam Ventures[47], such was not allowed but in Guang Xi Development v Sycal[48], failure to allow for a hearing in adjudication is contravening natural justice. Beside these ‘legal confusions’, CIPAA in its inception, as identified by CIDB is to ‘apply to all parties in the construction works, consultancy services and construction supplies in both government and private sectors’.[49] It is not only benefitting the contractors as ‘CIPAA can lead to better practices, greater integrity and efficiency’.[50] In reality, the unfolding events as prescribed by Harban as CIPAA is complicated, inefficient and lost its focus[51], brought with it ‘adverse consequences to the contractor and consultant’.[52] Now, CIPAA remains as seen as ‘toothless tiger’ or ‘winning on paper’ under such consideration. Foremost, as Chan asserted, not many aware that CIPAA is a 2-stage approach to successfully mount a claim, where (1) a favourable decision must be obtained; and (2) such decision is enforced in the HC.[53] Such 2-stage effects are not only ‘unaffordable’ it goes against the fundamental principle of CIPAA for ‘cheap rough justice’. BC’s hypothetical doubts of what are the remedies provided in CIPAA in the event of payment disputes’[54], is irrelevant, as ‘application to the courts, to obtain the writs of seizure and sale; garnishing proceedings and so on’ are expensive endeavours and rightly, CIDB pointed out that ‘lawyers are far from being out of work’ in the attempt to contemplate is ‘CIPAA will lead to a reduction in arbitrations and litigations and corresponding work for the lawyers’.[55] Whether with CIPAA, ‘will payment-default no longer be an issue’? The textbook answer, ‘no one can guarantee payment defaults will no longer be an issue’ remains relevant.[56] Thus, the next rationale question is why? Perhaps, revisiting Lam’s contention, as to how relevant are these hypothetical doubts against the unfolding events post 2014, which is no longer hypothetical? The Recent Development CIPAA is a going concerns and it is going to stay for another decade or so. Holding to Harban’s assertion, CIPAA is complicated, inefficient and lost its focus[57], it is no longer a ‘affordable’, ‘fast and furious’ access to ‘rough justice’. These ‘rough justice’ of ‘pay first, argue later’, as Justice Lee Swee Seng pointed out, is now, ‘fine justice’ of ‘argue, argue more and pay much, much later’.[58] J. Lee quick to make reference to Steve Jobs’s, quote, ‘if you define the problem correctly, you almost have the solution’ as a way forward for CIPAA. So, what the problem is? (1) Complication: In appointing adjudicator, as in Zana Bina v Cosmic Master Development[59], it was held that party who participated fully in an adjudication proceeding without raising any objection as to the validity of the adjudicator’s appointment during the proceeding was estopped from raising the objection subsequently in its setting aside application. Yet, the dust is not yet settled, as the issue arises whether the parties must first attempt to agree on an adjudicator before a request for nomination from the Director of AIAC? Short answer, no.[60] In suing the consultant architect, arising from a recoupment of a failed CIPAA adjudication in Leap Modulation v PCP Construction[61], the losing party commence another proceeding suing the architect in L3 Architects v PCP Construction[62], citing the classic common law case of Sutcliffe v Thackrah[63]. This set in motion the precedent that consultants are ‘immune’ from being sued by contractors as unlike in Sutcliffe, there is no privity of contract between the contractor and the architect, and thus there is no proximity as to the architect to render its duty of care. In understanding technical term, such as ‘storey’ to also include basement, as in Tan Sri Dato' Yap Suan Chee v CLT Contract[64] the meaning of storey was referred to the Uniform Building By-laws 1984 to also include basement, thus not necessarily floor above ground. Similarly, the term ‘occupation’ must be given the widest interpretation to include residential or commercial as in Liew Piang Voon v WLT Project Management[65]. (2) Monopoly: On the absent of the Director to appoint adjudicator, there has been a vacuum in the Directorship of the AIAC[66] when the former AIAC-Director was charged for alleged Criminal Breach of Trust (‘CBT[DYTW1] ’), leading to his resignation.[67] In this case of Sundra Rajoo v Minister of Foreign Affairs[68], Rajoo has since been acquitted due to his immunity[69] having being defended by AALCO on the basis of ‘exterritorial’[70], ‘functional necessities’[71] and ‘representative’[72].[73] However Rajoo’s case[74] demonstrated the conundrum faced by the Malaysian government, as argued by Thomas, such an immunity has placed the former AIAC-Director, above the law even above the Ruler.[75] But such impasse has left a dent in AIAC, being the sole appointing body for CIPAA adjudication, thus as Lam’s concerned, ‘CIDB is in control of registering and appointing adjudicators’[76], is in actual fact has no implication whatsoever, as it is irrational to actually vested upon a single appointing body for such a noble task. On the AIAC’s locus standi, as more cases move up to the court, as in Leap Modulation v PCP Construction[77], the court has gone as far as to interject the manner and efficacy of CIPAA in dispensing ‘rough justice’ and to the nature of AIAC being a ‘foreign entity’ with very little or no ‘check and balance’ self-regulation, had a monopoly grip on the dispensation of justice in Malaysia, no matter how ‘rough’ it is.[78] The AIAC has since taken the same matter to the Federal Court to have this portion of the judgement expunged.[79] The fate of CIPAA, while having put ‘off tangent’ from its initial purposes with more and more inconsistent and unpredictable judgements from the court, was plagued by alleged corruptions resulted in the former Director of the AIAC being replaced, based on the detailed insider content of just a ‘poison-penned’ letter.[80] On the Director’s locus standi, in Mega Sasa v Kinta Bakti[81], the plaintiff seeks to set aside the adjudication decision on ground that the adjudicator’s appointment was not valid for the reason that the appointing director of the AIAC has no locus standi in view that his position as the Director of AIAC is not legitimate in accordance to the Asian African Legal Consultative Organisation (‘AALCO’) Host Country Agreement. However, the HC held that CIPAA does not violate Article 8(1) Federal Constitution. It also rejected the challenge, that CIPAA is a ‘usurpation of the judicial power of the court’ in violation of Article 121 Federal Constitution, reason being CIPAA is a judicial function and not a replacement of the courts' judicial power. It further affirmed that the acting director had the power and duty to appoint the adjudicator, regardless if his position as the ‘director’ has yet to be finalized. (3) Over Legalistic: On answering the right question wrongly and the other way around. Courts are not concerned with merits or correctness of the decision.[82] This include, erroneous assessment of documentary evidence.[83] Therefore, Adjudicators are not bound by the disputes referred to them in the exact way as pleaded by the parties, especially with regard to the remedies sought.[84] However, the recent JKP v Anas Construction[85] holds that adjudicator must only and narrowly look at the actual contractual provision pleaded by the parties and not stray away with its own finding, even if in his opinion there are other contractual provisions that are more aptly relevant to the claim, as provided as evidence, failing which contravening natural justice. Similarly, the adjudicator must not in his own effort, investigate onto the validity of the evidence presented although CIPAA allows for inquisitorial proceeding as demonstrated in Cescon Engineers v Pesat Bumi[86]. The sum of these account for answering the wrong question rightly, thus where is the ‘fine line’? Similarly, there were risks where ‘expert construction adjudicator’ not schooled in law, ‘make new contract provision’ for the parties, without even realising it[87], thus how to draw the line of committing a ‘mistake in law’ and yet not fatal? On being the ‘legal playground’, CIPAA originally intended to be ‘fast and furious’ dispensation of justice by construction expert to construction stakeholders, but it has since morph into a ‘legal arena’ as ‘mini arbitration’, ‘mini trail’, ‘document only arbitration’ or even ‘fast track arbitration’, as J. Lee implied, it is ‘fine justice’ now. AIAC (2021) latest statistic shows, CIPAA from its humble beginning of 29 cases (2014), peaked to 816 cases (2019) and then dropped to 530 (2021), indicated the downhill movement of CIPAA, as Harban observed to be unaffordable, complex and ineffective[88], where majority of the parties’ representatives are law firms.[89] There may be truth, as Ali argued, ‘lawyers (experience) can be helpful in addressing issues in construction arbitrations or mediations while some may be unhelpful as insinuated by PAM and the NSW Act’.[90] Ali suggested that ‘training for robust adjudicator with high standard is needed’, yet the question is can such be outsourced instead of being monopoly by a single authority? More aptly, unhelpful lawyers are promoting robust ‘guerrilla tactics’ in taking a ‘second bite of the cherry’, post adjudication response, by seeking for a hearing to present the ‘questions of law’ previously not canvass, citing View Esteem and ‘hold ransom’ of the adjudicator citing Guang Xi Development v Sycal[91], failure to allow for a hearing in adjudication is contravening natural justice. In another adjudication case[92], a party representative represented by a law firm, requesting the adjudicator to ascertain the quantum of work done without even providing the site progress report or reliable consultant’s certification and attempt to set aside the Decision, citing the adjudicator failed to prompt the party as to what documents required.[93] This, again a classic example of lawyers, not technically trained, baffled by the technical construction requirements and norms. On being a robust defender, another kind of ‘guerrilla tactics’ employed as robust defence is the systematic use of Statutory Declaration (‘SD’) in lieu of ‘real concrete evidence’, as Premaraj observed, ‘to be the weakest form of evidence’[94] mirrored one being observed in Cempaka Majumas v Ecoprasinos Engineering[95], where the court finds, the adjudicator has the power not to take into consideration of the SD. Such tactics has through time, evolved to even launching a ‘police report’ citing the possibility of fraud, to compel the adjudicator that he has no jurisdiction to preside over the matter involving criminality, which is again, unfounded as the ‘presumption of innocent’ is the underlying doctrine of natural justice.[96] On being territoriality, in the case of Tekun Cemerlang v Vinci Construction Grands Projects[97], West Malaysia lawyers are prohibited to represent disputants in CIPAA Adjudication where the seats are in Borneo.[98] The repercussions spark suggestion that unlike arbitration, statutory adjudication has no seat.[99] Such opinion rely on the provision of CIPAA[100]. It would have been ‘less complicated’ if lawyers are not involved, as rightly demonstrated in Cempaka Majumas[101] where the court held the position of a ‘Claim Consultant’ as party representative did not contravene s.8 of the Sarawak Advocates Ordinance. On over complying with timeline, sheer confusion as to the meaning of ‘Working Day’ previously construed as where the site is located, instead the HC held that the ‘Working Day’ for the delivery of the Adjudicator’s Decision must be construed as the ‘working day’ of where the Adjudicator’s office is located.[102] This area of law is unsettled. As to the definition of “Date” in s.5(2)CIPAA must necessarily mean “a calendar date or a statement by which the due (calendar) date for payment is capable of being identified” and not simply, “immediate” for “instantly”, “promptly”, “forthwith”, “at once” or “straight away”.[103] On another matter, commencement of adjudication is upon appointment of adjudicator as compared to serving of the notice of adjudication.[104] The issue is made murkier when it is textbook provision that CIPAA has a strict timeline compliance, i.e. in Skyworld Development v Zalam Corporation[105] a day late ultimately rendered the Decision void, but in another case, adjudicator must not act fast to quickly dismiss the adjudication response if it is served even a day late, citing View Esteem. Whereas in Utama Motor Workshop v Besicon Engineering Works[106], the ‘hair splitting’ argument of term “make” is distinguishable from the word to “deliver” and to “release”, as the court held that when an adjudicator “makes” an adjudication decision is a question of fact and very much depends on the date stated on the first and last pages of the adjudication decision.[107] This applied to some instances where the site in question is ‘outstation’ and via AR-Registered Post, no one from the other side has attempted to receive the Hard-copy Decision, yet the manner of serving notices hold. Yet another case, in Itramas Technology v Savelite Engineering[108], the court held that there was actual bias by the Adjudicator for failing to give effect to the MCO[109], thus the question whether it is important to stick to the strict timeline of CIPAA or to allow for ‘reasonable’ flexibility? On being ‘flip-flopped’, in MIR Valve v TH Heavy Engineering[110], it is held that ‘ship building’ contract is excluded from CIPAA within the meaning of “construction work”. The similar judgment is held for YTK Engineering Services Sdn Bhd v Towards Green Sdn Bhd [2017], where a shipping contract or a mining contract does not fall within the meaning of “construction work” under s.4, CIPAA. But, in a platform-anchored into the land, is adjudicate-able[111], where interestingly J. Lim Chong Fong, then held, as observed by Sandrasegaran and another, ‘he was (1) not bound by his own prior views [inclusive of the quoted passage in Mir Valve which he was referred to]; and (2) capable of adjudging the case impartially despite the aforesaid’.[112] The issues and concerns raise here as the recent developments, are not exhaustive, as CIPAA has enter into its ‘volatile zone’, plagued with multitude of problems that at any one time, the construction stakeholders including the legal fraternity will dispose-off CIPAA for litigation and or arbitration, not discounting the birth of ‘expert determination’ on the Malaysian soil, where it is currently at its infancy, as cited by Rajoo, is ‘without any legal-baggage’, straight forward without a need for ‘reasoned decision’, even more ‘faster and more furious’ and legally binding.[113] The trend of CIPAA, as observed by COA J. Lee Swee Seng, at the KL HC seeking to be set aside and or enforced, under s.28, CIPAA, as of 30 Sep 2022, allowed (58%), disallowed (11%) and discontinuation (22%); while seeking to be set aside and or enforced, under s.15, CIPAA, as of 30 Sep 2022, are allowed (11%), disallowed (50%) and discontinuation (32%); and set aside and or enforced, under s.16, CIPAA, as of 30 Sep 2022, are allowed (4%), disallowed (35%) and discontinuation (38%),showing a pro-adjudication approach taken by the court.[114] Perhaps it is also timely to revisit CIDB’s Initial Proposal, for a solution in structural, procedural and institutional reform of CIPAA. Conclusion This discourse starts by asking, does the creation of the Construction Court and CIPAA resolved the construction industry’s conundrum? The discussion thus commence with looking at the ‘roller coaster’ of long hauled ‘gestation’ since 2003 to make CIPAA a reality in 2014, where the implemented version was not as envisioned by the construction stakeholders but by the legal fraternity with the AIAC, all that came about from the ‘hypothetical doubts’. Further discussion pointed to the growth stage that witnessed the ‘disjointed’ comprehension of this piece of jurisprudence as ‘design intended’ by the AIAC with that of another version as interpreted by the upper courts, notably precedent set in View Esteem, changing the course of CIPAA into ‘disarray’. This follow by peeling into the current state of the CIPAA ‘affairs’ coupled with ‘incidental events within AIAC’ and the effects of the pandemic, to draw upon the ‘correct definition of the problem and with hope, the solution will almost surface within’ as predicted by Steve Job. So, what the problem is, but of (1) Complication; (2) Monopoly; and (3) Over Legalistic, generating the ‘push effect’ of the construction stakeholders away from CIPAA notwithstanding the pro-adjudication approach taken by the court. With the amount of stockpile of cases in court, as compared to the other forms of ADR, it is testimony of the amount of curial intervention invested into CIPAA. So, does the creation of the Construction Court and CIPAA resolved the construction industry’s conundrum? Obviously, NOT. Now, in the turbulence of the waves in the ocean of law, we are forced to look back to the ‘star’ for guidance and seek the ‘compass’ that we had so conveniently cast away, to guide the CIPAA vessel to its next destination of glory in the following area of structural, procedural and institutional reform, asking the question, what can be done? Not exhaustive as this may be, the followings are the area we could improve on: (1) Structural Reform On triangulated relationship[115], among curial intervention, the disputing party and the adjudicator, it is important for the court to wholly submerged into the core objectives of CIPAA, identified as the 4 key features in the CIDB’s version[116], where the interpretation of the Act takes into the perspective of ‘rough justice’ and not ‘fine justice’, in the hope that the decision as in the View Esteem be reversed. Having considered that, the issue on res-judicata[117], as in ‘procedural res-judicata’ must be eliminated as CIPAA is only temporary finality, but in Samsung C & T Corporation v Bauer[118], the doctrine applies to where the portion of the claims that had been adjudicated must not be re-adjudicate.[119] Similarly so, this doctrine apply to presentation of documents, previously not presented.[120] Similarly, technical issues best resolved by technical people, excluding lawyers if the other party is not represented by lawyer[121] and adjudicators are technical professionals that need to be legally trained.[122] In that manner, over legalistic issues as mounted in Integral Acres v BCEG International[123] would not have surfaced in the first instance. Coupled with this, there should be decentralisation of training and appointing of adjudicator via the various institution of the construction stakeholders[124], also to include publishing of the sanitised version of the Decision, to add to the feedstock of knowledge in adjudication[125]. (2) Procedural Reform On streamlining and shortening of the procedure and time of delivery of Decision, mirrored the draft SOPL (Hong Kong)[126], both the Payment Claim or Response, are considered the Adjudication Claim and Response as there is only Claim, Response and Reply with no further ad hoc mechanism required.[127] The current curial discouragement of hearings[128] and rejoinders[129] coupled with a simple yet ‘bullet proof’ approach to making the decision[130] in CIPAA must be maintained, i.e. suffice to say, ‘[incline] to agree/disagree or persuaded/not persuaded’ as reasons, as court held finding of facts cannot be challenged[131]. On putting a limit for adjudication. CIPAA must not be a ‘forum convenience’ to contemplate complex issues such as ‘final account’[132] and should well deal with all matters interim in nature[133], bar from adjudication upon issuance of certificate of substantive completion or practical completion, leaving the rest for arbitration or litigation. There should also be a cap value of dispute as Harban argued, the current adjudicator’s fee enshrined in Act are downright discouraging[134] and only a dispute reaching a certain threshold can be adjudicated and such also include properties owned by a single individual or for its own dwelling at any storey[135]. Similarly so, the Act should allow the creation of an stakeholder’s account where the disputed sum must be mandatory deposited prior to adjudication[136], as this will once and for all encouraged ‘pay first argue later’[137], hopefully achieving the objective that payment default is a matter of the past[138]. Learning from the pandemic, email communication must be mandated and any timeline, be best taken to be flexible within the 100-days framework[139]. Where permitted, contractual adjudication must be allowed as in the construct of the DRS/DRA[140], in line with the other ADR mechanism and in other word, this Act can be contracted out provided party has pre-agreed to any forms of contractual adjudication[141]. (3) Institutional Reform On institutional intervention, AIAC could maintained its role, instead of overseeing the training, appointing and administering CIPAA adjudication, to making policy and monitoring the other allied institutions that have contracted out with such role of the training, appointing and administering CIPAA adjudication, while constantly provide a seamless platform with the judiciary to iron out any ‘wrinkles’ in the interpretation of the Act, while collecting annual prescription from the outsourced institutions. The inclusion policies will mutually benefitted construction stakeholder institutions and not looked upon as a ‘legal playground’ befitting only the legal fraternity. Such is glaring when the AIAC has stopped providing information pertaining to the professional background of adjudicators empanelled with the AIAC, in 2016 indicated lawyer (177); Engineer (59); Architect (11); QS (51); and Others (65), indicating an imbalance participation of technical people in adjudication.[142] These arguments and proposals, as put forward, are not exhaustive as all kinds of issues are now, pushed back to the court for decisions, aptly taken as the ‘knowledge gap’ or limitation for this critical observation; also not limited to the fact and caveat that this is not a legal advice and the views made in this articles are of the personal view of the author, made for academic purposes without commercial value, based on published materials. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- [1] Lam, ‘Latest Development in CIPAA and Adjudication Law’, (20 Nov 2021), L2-series: reported 2018-2021, +200 cases reported and 2020 alone, +100 cases reported, far exceeded arbitration case report; AIAC Annual Report 2019-2020: Oct 2021, 200 reported cases in the HC; 2020, 100 reported cases in the HC; 537 cases registered with the AIAC. [2] Alternative Dispute Resolution (‘ADR’). [3] Cheang, ‘A Study of the Effectiveness of the Malaysian CIPA Act vis-à-vis the Impact of Oversea Construction Payment Legislation on their Respective Construction Industries’ (BSc.QS, 2017, UTAR), p.36: citing KLRCA Annual Report (2016). [4] Chan, ‘CIPAA update – A case of creeping complexities?’, (3 Jul 2019), <https://www.cipaamalaysia.com/blog/cipaa-update-a-case-of-creeping-complexities>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [5] Ali [n17], p.4-22. [6] Chan, ‘Test for Bias Against an Adjudicator’, (9 Aug 2021), <https://www.cipaamalaysia.com/blog/test-for-bias-against-an-adjudicator>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [7] [2018] 1 CLJ 536. [8] [2020] 9 MLJ 499 [9] [2016] MLJU 1567. [10] [2021] 9 MLJ [11] ADJ-4341-2022; ADJ-4374-2022 [12] Rosha Dynamic Sdn Bhd v Mohd Salehhodin bin Sabiyee & Ors and other cases [2021] MLJU 1222 [13] [2017] 1 LNS 1378. [14] Foo, ‘CIPAA Adjudication: What has Changed since View Esteem Sdn Bhd v Bina Puri Holdings Bhd’ (27 Sep 2018), <https://www.ganlaw.my/embrace-the-storms-of-the-movement-control-order-mco-2/>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [15] Ibid. [16] Ali [n14], p.20: Question 13. [17] Ali [n14], p.17: Question 9. [18] [2017] 1 CLJ 101: The Federal Court in its grounds of judgment dated 1 August 2019 in Martego Sdn Bhd v Arkitek Meor & Chew Sdn Bhd decided on important points of law on adjudication and final payments under a construction contract. https://themalaysianlawyer.com/2019/08/13/case-update-federal-court-decides-on-final-payments-adjudication/ [19] Integral Acres Sdn Bhd v BCEG International (M) Sdn Bhd and other cases [2021] MLJU 1889 [20] Ali [n14], p.20: Question 13. [21] Lam [n18], p.13. [22] Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia [Malaysia Institute of Architects] (‘PAM’). [23] Ali [n14], p.21: Question 16. [24] The Malaysian Lawyer, ‘CIPAA: Adjudication Leading the Way?’, <https://themalaysianlawyer.com/2018/09/05/cipaa-adjudication-leading-the-way/>, accessed 1 Nov 2022: cited the Malaysian Law Conference 2018. [25] Foo [n 39]. [26] Jack-In Pile (M) Sdn Bhd v Bauer (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd [2020] 1 CLJ 299: FC puts an end to this long-haul debate, by holding that CIPAA to be applied ‘Prospectively’. [27] Bina Puri Construction Sdn Bhd v Hing Nyit Enterprise Sdn Bhd. [2015] 8 CLJ 728: In the absence of certification, the non-paying party cannot deprive the unpaid party from availing the adjudication process. [28] Likas Bay Precinct Sdn Bhd v Bina Puri Sdn Bhd [2019] MLJU 49: it was held by the Court of Appeal, that a successful claimant in adjudication need not have the adjudication decision registered before issuing a statutory notice of ‘winding up’; finding in contras, ASM Development (KL) Sdn Bhd v Econpile (M) Sdn Bhd (Case No. WA-24NCC-363-07/2019): High Court granted an injunction restraining ‘winding up’. [29] Ireka Engineering & Construction Sdn Bhd v PWC Corporation Sdn Bhd [2020] 1 MLJ 311: the term contract in CIPAA refers to ‘singular’ contract and not ‘contracts’; finding in contrast, Punj Lloyd Sdn Bhd v Ramo Industries Sdn Bhd & Anor and another case [2019] 11 MLJ 574: contract by reference is a singular contract. [30] Yek, ‘My SOPL: Security of Payment Legislation in the Malaysian Construction Industry, My Observation’, (15 Aug 2019), <http://www.davidyek.com/adr/my-sopl-security-of-payment-legislation-in-the-malaysian-construction-industry-my-observation>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [31] [2008]4CLJ175. [32] Civil Appeal:02(i)-35-04/2019(W). [33] Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967,s.12; see also <http://www.davidyek.com/adr/serving-of-notice-and-documents-in-cipaa-adjudication-where-is-the-norm-now>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [34] Ali [n14], p.16: Question 8. [35] Lam [n18], p.13. [36] PAM Form 2018, cl.36: Adjudication. [37] Rajoo and others, ‘The PAM 2006 Standard Form of Building Contract’, (LexisNexis,2010), p.828:citing Dean v Prince (1954) 1Ch409. [38] [2015] 1 LNS 1435. [39] Ali [n14], p.17: Question 9. [40] [2017] MLJU 2381 [41] Kuasatek (M) Sdn Bhd v HCM Engineering Sdn. Bhd and other appeals [2018] MLJU 1919 [42] Integral Acres Sdn Bhd v BCEG International (M) Sdn Bhd and other cases [2021] MLJU 1889 [43] Sunissa Sdn Bhd v Kerajaan Malaysia & Anor [2020] MLJU 283 [44] The Malaysian Lawyer [n 49]. [45] The Malaysian Lawyer [n 49]. [46] Try everything you can in order to do something or to solve a problem, <https://languagecaster.com/football-cliche-throw-the-kitchen-sink>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [47] [2020] 1 LNS 145 [48] [2018] MLJU 1542 [49] Ali [n14], p.14: Question 2. [50] Ali [n14], p.14: Question 3. [51] The Malaysian Lawyer [n 49]. [52] Ali [n14], p.16: Question 7; p.15: Question 6. [53] Chan [n 29]. [54] Ali [n14], p.18: Question 10. [55] Ali [n14], p.22: Question 18. [56] Ali [n14], p.23: Question 19. [57] The Malaysian Lawyer [n 49]. [58] COA J. Lee Swee Seng’s opening remark on ‘CIPAA conference in Asia ADR Week 2022’, AIAC Kuala Lumpur; see also <https://www.linkedin.com/posts/asian-international-arbitration-centre_asiaadrweek2022-aadrweek2022-aiaccompassus-activity-6984378475428159489-jjZi/>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [59] [2017] MLJU 146 [60] KLIA Associates Sdn Bhd v Mudajaya Corporation Berhad [2020] 1 LNS 1253 [61] [2018] MLJU 772. [62] [2020] MLJU 972 [63] [1974] AC 727 [64] [2021] MLJU 1964 [65] [2020] 1 LNS 1105 [66] Borneo Post,‘Urgent need to appoint AIAC director–SLS’, (7 Jul 2020) <https://www.theborneopost.com/2020/07/07/urgent-need-to-appoint-aiac-director-sls/>,accessed 15 Dec 2021. [67] Edge,’AIAC director resigns over MACC investigation’, (22 Nov 2018), <https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/aiac-director-resigns-over-macc-investigation>, accessed 20Dec2021. [68] [2021]Civil Appeal: 01(f)-38-12-2020(W), at 112. [69] Rajoo [n 93]. [70] Temporary premises of a sovereign in a foreign jurisdiction were perceived to be an extension of the territory of the sending State. [71] Immunities as being necessary for the mission to perform its functions. [72] Mission personifies the sending State. [73] AALCO, ‘Immunity of State Officials From Foreign Criminal Jurisdiction’, (10 Apr 2012), IMLE <https://www.aalco.int/Background%20Paper%20ILC%2010%20April%202012.pdf>, accessed 27 Dec 2021. [74] Rajoo [n 93]. [75] Malaysiakini,‘Thomas: Legal immunity puts ex-AIAC director above rulers’,(6Nov2021) <https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/598081>,accessed 27Dec2021;Thomas,‘My Story:Justice in the Wilderness’(GerakBudaya,2021)pp391-399. [76] Lam [n18], p.13. [77] [2018] MLJU 772 [78] <https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/465089>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [79] Ibid. [80] “AIAC director resigns over MACC investigation”, Edge Markets, <https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/aiac-director-resigns-over-macc-investigation>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [81] [2020] 4 CLJ 201; also see Prestij Mega Construction v Estate of Vinayak Pradhan BA-24C-13-02/2020 and BA-24C-25-03/2020 [82] Maju Holdings Sdn Bhd v Spring Energy Sdn Bhd [2021] 8 MLJ 275; Acoustic & Lighting System v Les Engineering [83] Ong Teik Beng (t/a MJV Construction) v Wow Hotel Sdn Bhd [2022] 8 MLJ 10 [84] First Commerce v Titan Vista [2021] MLJU 376. [85] [2022] MLJU 2124 [86] [2022] 9 MLJ 79 [87] Perbadanan Perwira Harta Malaysia v Kuntum Melor Sdn Bhd and another case [2021] MLJU 1593 [88] The Malaysian Lawyer [n 49]. [89] AIAC Annual Report 2021-2022. [90] Ali [n17], p.17: cited Geoff Bayley’s experience in New Zealand adjudication. [91] [2018] MLJU 1542 [92] AIAC/D/ADJ-4341-2022 [93] HST Engineers v PauYuan Sdn Bhd [2022], unreported. [94] Premaraj, ‘CIPAA Webinar series on Practical Tips and Must-Have Records for Employers to Succeed in CIPAA’ (16 Jun 2022), <https://www.linkedin.com/posts/belden-advocates-%26-solicitors_welcome-you-are-invited-to-join-a-webinar-activity-6933256995030351872-yBrg?>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [95] [2019] (BTU-24C-2-7-2018). [96] ADJ-4210-2022 [97] [2021] 11 MLJ 50 [98] s.15, Advocates Ordinance (“AO”). The finding of the HC is in contrast with the provision of CIPAA (Section 8(3) of the CIPAA provides that parties to an adjudication proceeding “may represent himself or be represented by any representative appointed by the party”. [99] Chaw G, “Statutory Adjudication in Malaysia and ‘Sabah Proceeding’: A Paradox”, [2021], 3 MLJ, p.10: the concept of a ‘seat’, which is part of the legal framework of arbitration law, does not exist in the law and practice of adjudication. [100] ss 13, 15 and 16 CIPAA 2012 [101] [2019] (BTU-24C-2-7-2018). [102] Encorp Iskandar Development Sdn Bhd v. Konsortium Ipmines Merz Sdn Bhd [2020] 1 LNS 1129 [103] Perbadanan Perwira Harta Malaysia v Kuntum Melor Sdn Bhd and another case [2021] MLJU 1593 [104] Granstep Development Sdn Bhd v Tan Chong Heng & Ors [2020] MLJU 2364 [105] [2019] 1 LNS 173 [106] [2022] 7 CLJ 313 [107] Celtex Supreme Sdn Bhd v Mega Bina Garisan Sdn Bhd [2021] 1 LNS 630 [108] [2021] MLJU 1382 [109] Movement Control Order (‘MCO’): measures taken under the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Regulations 2020 [PU(A)91/2020] [110] [2017] AMEJ 0538 [111] E.A Technique v Malaysia Marine and Heavy Engineering [2020] WA-24C-96-06/2019 [112] Sandrasegaran and other, ‘E.A Technique (M) Berhad (“EAT”) v. Malaysia Marine and Heavy Engineering Sdn Bhd (“MMHE”)’, (18 Jul 2020), <https://mohanadass.com/publications/articles/ea-technique-m-berhad-eat-v-malaysia-marine-and-heavy-engineering-sdn-bhd-mmhe.html>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [113] Rajoo and others,‘Standard Form of Building Contract Compared’(LexisNexis,2022),p456: cited FIDIC RB2017, sub cl.3.7.5, prescribed the Officer’s decision, in form is ‘expert determination’, similarly to PWD203A. [114] Lee [n 83]. [115] Mirrored the findings of Pryles, ‘Limits to Party Autonomy in Arbitral Procedure,’ (2007), 24 AJA, pp.327–339. [116] Ali [n14], p.7-10. [117] Macly Equity Sdn Bhd v Prestij Mega. Construction Sdn Bhd [2021] MLJU 537 [118] [2019] MLJU 1690 [119] PJ Midtown Development Sdn Bhd v Pembinaan Mitrajaya Sdn Bhd and another summons [2020] MLJU 1432 [120] Puncak Niaga Construction Sdn Bhd v Mersing Construction &. Engineering Sdn Bhd and other cases [2021] MLJU 1824 [121] Ali [n14], p.21: Question 16. [122] Ali [n14], p.21: Question 15. [123] [2021] MLJU 1889 [124] Ali [n14], p.21: Answer15. [125] Ali [n14], p.21: Answer17. [126] Yang, ‘Hong Kong's Contractual Security of Payment (SOP) Regime for Public Works Contracts‘, (2021), <https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=e948ad6b-fa58-4fcb-a8fe-4ae811406024>, accessed 1 Nov 2022. [127] Ali [n14], p.21 Question 14. [128] MRCB [n 72]. [129] Ireka Engineering & Construction Sdn Bhd v. Tri Pacific Engineering Sdn Bhd and another [2020] MLJU 548 [130] Dekinjaya Builder Sdn Bhd v Chong Lek Engineering Works Sdn Bhd and another case [2020] MLJU 2455 [131] Mei He Development Sdn Bhd v Eosh Industries Sdn Bhd [2021] MLJU 519 [132] Ali [n14], p.20 Question 13. [133] Ali [n14], p.18 Question 10; p.17-18 Answer 9. [134] Harban, ‘CIPAA conference in Asia ADR Week 2022’, AIAC Kuala Lumpur. [135] Ali [n14], p.16 Question 8. [136] Ali [n14], p.21 Answer 14. [137] Ali [n14], p.14 Answer 3; p.15 Answer 5; p.16 Answer 7. [138] Ali [n14], p.23 Answer 19. [139] Ali [n14], p.19 Answer 12. [140] Dispute Resolution Board (DRB)/ Dispute Resolution Advisor (DRA) [141] Ali [n14], p.19 Answer 11; p.22 Answer 18. [142] Cheah, ‘Adjudication’, (1 Aug 2019), Joint Courses on Alternative Dispute Resolution for Practitioners by IEM + MIArb + RISM + PAM, p.24. SERVING OF NOTICE AND DOCUMENTS IN CIPAA ADJUDICATION – WHERE IS THE NORM NOW? UPDATE: On 4 Apr 2022, the AIAC has issued circular 11, prescribing manner of serving notices, adopted for CIPAA 2012. Apparently, s.38(a)-(d),CIPAA 2012, wasn’t that definitive when comes to the recent findings of the courts as in Skyworld Development Sdn Bhd v Zalam Corp Sdn Bhd[1], where delivery of AR-Registered is presumably delivered unless rebutted. Here, the definition of ‘delivery at its ordinary course’ does not imply the ‘date of posting’. Such, sender has to provide ‘sufficient period of time’ for delivery, as in regard to s.38(c), CIPAA 2012: Service by Registered Post. Applying such to serving of Payment Claim, Notice of Adjudication and other Notices including the Decision, the ‘actual receipt’ of such notices is indicated. It is manifested that the AIAC attempted to provide clarity, but it dropped short of specifying what does it mean by ‘sufficient period of time’? Compounded by the absent of clarity as to what it meant by ‘indicate’ and ‘acceptance’ in the Interpretations Act 1948, the burden now, rests squarely on the shoulders of the Adjudicator. ----------------------------------------------------- [1] [2019] MLJU 162 Assuming that Claimant had filed a Request to Appoint an Adjudicator and the Adjudicator had proposed his terms of appointment, with only the acceptance by the Claimant agreeing that communication is via email. Respondent has not responded at all. The Adjudicator then emailed and couriered his Notice of Acceptance via Form-6 on the last working day i.e. day-10. The parties would not have possibly receive the physical Form-6 by then.

The questions were whether failure of the parties receiving the physical Form 6 within the 10 working days constitute a breach of s.23(2) CIPAA? If so, what constitute the manner of serving of notices? The law holds: S.23(2) CIPAA states, “The adjudicator shall propose and negotiate his terms […] within ten working days from the date he was notified of his appointment, […]” S.38 CIPAA states, “Service of a notice or any other document under this Act shall be […] a) By delivering the notice or document personally […] b) By leaving the notice or document […] during the normal business hours of that party; c) By sending the notice or document […] by registered post; or d) By any other means as agreed in writing […]” The evidence shows: One, there is no mutual acceptance by the parties of the Adjudicator’s terms and communication via email. Thus, method of serving notice or document as prescribed under S.38 CIPAA prevailed. Two, parties would not have possibly received the physical Form 6 within then. So, whether such failure to receive the physical Form 6 constitute a breach of s.23(2) CIPAA? To answer this, can courier services be construed as hand delivery? If so, what constitute hand delivery? Ordinary meaning of courier, is a person or company that takes messages, letters or parcels from one person or place to another.[1] Whereas, hand delivery is to take something to someone yourself or send it by courier.[2] Therefore, a courier service can be construed as by hand. Thus some insisted that an affidavit be taken by the courier serviceman to affirm that the documents had been served. Implying such, it must be a recorded delivery. Three, parties may have received the document past the ‘normal business hours’. This condition is not warranted with regard to s.38(a). We are not clear who would have been there to receive it past the ‘normal business hours’? S.38(b) holds that document is deemed served ‘by leaving it at the usual place of business’, ‘during normal business hours’. This provision is in contrasts to the HC decision that a ‘day’ as in a ‘working day’ covers 24-hours.[3] Thus, if the documents were couriered within the same working day, duly recorded by statutory affirmation or recorded delivery, it is deemed to have been delivered. Concluding: Whether failure of the parties to receive the physical Form 6 within the 10 working days period constitute a breach of s.23(2) CIPAA, the short answer is depends on the merits. It is in breach, if the courier is of an unrecorded delivery or with no statutory affirmation, delivered outside the last ‘working day’. It is not a breach if the conditions and merits would had unfold otherwise. What constitute the manner of serving of notices? It is as prescribed by S.38 CIPAA either by hand delivery; leaving at the office during ‘business hour’; or via registered post; or by any other means agreed. Having considered that, assuming the Adjudicator sent the notice by registered post instead of courier, would the ‘postal rule’ applied? What is in the postal rule? The ‘postal rule’[4] and communication via email[5] are commonly applied in contractual transaction. In postal rule, communication deemed to have occurred once the letter has been posted (registered). However, email is not governed by this postal rule.[6] Malaysia has similarly adopted this postal rule via application of the s.4(2)(b) Contract Law 1950.[7] However, can this postal rule also applied in Adjudication? Two contrasting approaches, with regards to ‘postal rule’. As applied observed in the serving of writ of summons via AR-Registered Post, on one hand, there is no provision of law that Plaintiff must prove that the named person had received the writ of summons and statement of claim, being sent by AR-Registered Post, unless rebutted by Defendant.[8] On the other, affidavit of service must prove ‘due service’ of writ of summons and that the lacuna of the Rules of Court 2012 (“ROC”)[9] must be interpreted in favour of the Defendant.[10] This unsettled law was revisited by the courts recently, contemplating whether the acknowledgement of AR-Registered Post receipt card is conclusive proof? The HC and Court of Appeal hold that it was conclusive prove. The FC disagree and went on to say, AR-Registered Post receipt card is not conclusive if the affidavit does not exhibit the receipt card does not contain an endorsement of receipt by the Defendant or nominee.[11] Adjudication mirrors the conduct of the court. Can the Adjudicator simply drop the notice off at the post office and call it a day? In reflection of Goh Teng Whoo case[12] the short answer is ‘No’. Service by way of AR-Registered Post does not conclusively mean that the recipient has received the same as the AR-Registered Post, continues to be interpreted as ‘service and time’ of service are ‘presumed’ and ‘until the contrary is proven’.[13] We have yet to see this judgement be applied to an Adjudication case. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- [1] Cambridge Dictionary <https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/courier> accessed 3 Nov 2021 [2] Cambridge Dictionary <https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/hand-deliver> accessed 3 Nov 2021 [3] Skyworld Development Sdn Bhd v. Zalam Corporation Sdn Bhd & Other Cases. [2019] 1 LNS 173 [4] Adams v Lindsell [1818] 1B&Ald.681 [5] S.7.Electronic Communications Act 2000; Neocleous v Rees[2019]EWHC2462(Ch) [6] Thomas v BPE Solicitors [2010] EWHC306(Ch); Greenclose v National Westminster Bank [2014] EWHC1156(Ch) [7] Ignatius v Bell (1913) 2 FMSLR 115 [8] Yap Ke Huat & Ors v Pembangunan Warisan Murni Sejahtera Sdn Bhd & Anor [2008] 4 CLJ 175 [9] Order 10 Rule 1(1) ROC [10] Chung Wai Meng v Perbadanan Nasional Berhad [2017] 1 LNS 892 [11] Goh Teng Whoo & Anor v Ample Objectives Sdn Bhd (Civil Appeal No: 02(i)-35-04/2019(W) [12] [2021] MLJU 300 [13] S.12 of the Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967 ADJUDICATION WITH THE SPANNER IN THE GEARBOX CIPAA Adjudication is no longer a dispensation of ‘rough-justice’ in a ‘fast-and-furious’ way. The true intention of CIPAA to expedite dispute-resolution as to enable contractor’s its life-source, which is payment, is off-tangent, into a ‘mini-trial’ or ‘mini-arbitration’, where counsels can actually test its evidence and arguments before going for a ‘final-resolution’, without giving ample ‘arsenals’ for the adjudicator to work on its own ‘competenze-competenze’; for a fee, far below of that of arbitration or the counsel’s own retainer, especially when ‘hearing’ is accorded.

CIPAA was once known to be of 88%-success rate for the Claimant, usually contractor, not until the first ‘spanner was thrown into the gearbox’, that Respondent has the right to raise defence at any point in time during the progress of CIPAA.[1] Claimant has 5-days to put in its Reply, taking advantage of this, the tactical- maneuvering of an ambush with documents in the Response, during prolonged ‘holiday-seasons’, left very little time for Claimant to Reply. Does the matter stop at Reply? The answer is ‘no’… for most adjudicator may find that the entire Response is dedicated to a ‘single-objective’, to ‘remove’ the adjudicator for the lack of jurisdiction to preside over the adjudication. Thus, request for further submission i.e. rejoinder, sur-rejoinder, rebuttal and sur-rebuttal are requested. Will a rational adjudicator obliged to allow such, fearing ‘lack of natural justice’ disposition? Usually the adjudicator will give-in, eating into his 45-days to serve its Decision. The story doesn’t ends there yet. There were attempt by counsel, usually Respondent, to seek for Hearing and Written-Submission.[2] Such call was turned down by the HC, keeping faithfully to the spirit of CIPAA, which is dispensation of ‘rough-justice’ in a ‘fast-and-furious’ way. Having said that, some Respondent will put in ‘Expert-Report’ as evidence, some by the cartons of A4-boxes, mirrored such as in arbitration or litigation, holding faithfully to View-Esteem’s ruling, in Response, Rejoinder and maybe Rebuttal. Should the adjudicator allowed for hearing to review these ‘Expert-Report’ evidence? That is like walking tip-toe at the tight-rope, requiring a fine-balancing act, fearing a breach of natural-justice. Alas, the Appeal-Court has then, opens a flood-gate, rendering breach of natural-justice if the adjudicator does not allow Hearing and Written-Submission, on the basis of insufficient time.[3] The second spanner was thrown into the gearbox, swinging the pendulum to the Respondent, as with Hearing and Written-Submission, the chances voiding the entire CIPAA processes are very high. There is yet, procedural aspect of Hearing and Written-Submission in a conduct of adjudication available in the adjudicator’s tool-boxes, especially so when the notion of competenze-competenze is absent. The stroke of genius on tactical-maneuvering for a ‘weak-case’ is vested upon the conduct of Hearing and Written-Submission, to prolong the processes and along the way, to nail the adjudicator for prejudice. Will the story ends here? Not likely. By this time, after serving the Claim, the adjudicator will more likely to call for a preliminary meeting, set the agenda for exchange of documents, fixing hearing dates and those procedural-rules that is common in arbitration, in place for adjudication which is a lacuna for a moment, for AIAC to pluck out the spanner from the gearbox. Wonder, is there additional adjudicator fee for hearing and such? ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- [1] View Esteem Sdn Bhd v Bina Puri Holdings Bhd [2017] 1 LNS 1378: <https://themalaysianlawyer.com/2018/09/05/cipaa-adjudication-leading-the-way> [2] MRCB Builders Sdn Bhd v. Wazam Ventures Sdn Bhd & Another Case [2020] 1 LNS 145 [3] GuangXi Dev & Cap Sdn Bhd vSycal Bhd [2018] MLJU 1542 THE SETTLE OF THE ‘UNSETTLED-LAW’ IN CIPAA AS AT 2020CIPAA apply prospectively[1] with “conditional-payment” enforceable for contract prior 15th April 2014[2]; not to be “contracted-out”[3]; rarely granted “stay of adjudication” unless for specific “narrow-reasons”[4] i.e. res-judicata[5] or pre-qualify for stay requires commencement of arbitration/proceeding[6]; zerorising Respondent’s claim[7]; “non-certified”[8] claims allowed; exempting government as disputing-party[9] but exclude item not of “national-security”[10]; consultancy-contract can be adjudicated[11] including final-account[12]; setting-aside under s.15[13] includes in-existence of an arbitration-award/judgement[14]; allow new defences post payment-response[15]; must accorded “hearing”, failing which “breach of natural-justice”[16]; no-appeal on “ground of law”[17], even there is an “error of law”[18]; exclude shipping[19] and mining[20] contract, but a platform-anchored into the land, is adjudicate-able[21]; estoppel of party participated fully to raise any-objection on adjudicator’s-appointment[22]; constitutionality of CIPAA upheld[23]; rights to limit extension-of-time for submission[24], including adjudicating-EOT as “contingent jurisdiction”[25], and L&E[26]; allowing claims of “pre-award” interest[27], only if such is claimed[28]; non-mandatory for decision to be registered prior serving ‘winding-up’[29], but cautionary apply to company on “disputed-debts”[30] owing to its “temporary-finality”[31]; non-interference of court to “vary adjudication-decision”[32], awarding-costs[33] nor “supplanting” adjudicator’s-order[34]; and mandatory for principal to pay[35].

---------------------------------------------------- [1] Jack-In Pile (M) Sdn Bhd v Bauer (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd [2020] 1 CLJ 299 [2] Jack-In Pile [2020] [3] Ranhill E&C Sdn Bhd v Tioxide [2015] 1 LNS 1435 [4] Subang Skypark Sdn Bhd v Arcradius Sdn Bhd [2015] 11 MLJ 818 [5] Samsung C & T Corporation & Anor v Bauer (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd [2019] MLJU 1690 [6] Foster Wheeler E & C (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd v Arkema Thiochemicals Sdn Bhd Anor [2015] 1 LNS 632; Punj Lloyd Sdn Bhd v Ramo Industries Sdn Bhd & Anor and another case [2019] 11 MLJ 574 [7] Tenaga Poly Sdn Bhd vs Crest Builder Sdn Bhd (unreported) [8] Bina Puri Construction Sdn Bhd v Hing Nyit Enterprise Sdn Bhd [2015] 8 CLJ 728 [9] Mudajaya Corporation Bhd v Leighton Contractors (M) Sdn Bhd [2015] 5 CLJ 848 [10] ENRA Engineering and Fabrication Sdn Bhd v Gemula Sdn Bhd & Another Case [2019] 10 CLJ 333 [11] Martego Sdn Bhd v Arkitek Meor & Chew Sdn Bhd & Another Case [ 2017] 1 CLJ 101 [12] Martego [ 2017] [13] Wong Huat Construction Co v Ireka Engineering & Construction [2018] 1 CLJ 536 [14] Prestij Mega Construction Sdn Bhd v Keller (M) Sdn Bhd & Other Cases [2019] 1 LNS 1612 [15] View Esteem Sdn Bhd v Bina Puri Holdings Bhd [2017] 8 AMR 167 [16] Guangxi Dev & Cap Sdn Bhd v Sycal Bhd & Anor Appeal [2019] 1 CLJ 592 [17] VVO Construction Sdn Bhd v Bina MYK Sdn Bhd Anor [2017] 2 AMR 502 [18] SKS Pavillion Sdn Bhd v Tasoon Injection Pile Sdn Bhd [2019] MLJU 1051 [19] MIR Valve Sdn Bhd v TH Heavy Engineering Berhad & Other Cases [2017] 8 CLJ 208 [20] YTK Engineering Services Sdn Bhd v Towards Green Sdn Bhd [2017] 5. AMR 76 [21] E.A Technique v Malaysia Marine and Heavy Engineering [2020] WA-24C-96-06/2019 [22] Zana Bina Sdn Bhd v Cosmic Master Development Sdn Bhd [2017] MLJU 146 [23] Amerin Residence Sdn Bhd v Asian International Arbitration Centre ([2019] 1 LNS 904; Mega Sasa Sdn Bhd v Kinta Bakti Sdn Bhd & Ors [2019] MLJU 1043; [2019] 1 LNS 1366 [24] Binastra Ablebuild Sdn Bhd v JPS Holdings Sdn Bhd and another case [2017] MLJU 1260 [25] SKS Pavillion Sdn Bhd v Tasoon Injection Pile Sdn Bhd [2019] 2 CLJ 704 [26] Syarikat Bina Darul Aman Bhd & Anor v Government of Malaysia [2017] MLJU 2381 [27] Milsonland Development Sdn Bhd v Macro Resources Sdn Bhd [2017] MLJU 169 [28] Naza Engineering & Construction v SSL Dev [2019] [29] Bina Puri Sdn Bhd v Likas Bay Precinct Sdn Bhd [2018] MLJU 864 [30] Maju Holdings Sdn Bhd v Spring Energy Sdn Bhd [2020] MLJU 1196 [31] ASM Development v Econpile [2019] WA-24NCC-363-07/2019 [32] Naza Engineering & Construction v SSL Dev [2019] [33] TRT Engineering (M) Sdn Bhd v Hansol KNM Greentech Sdn. Bhd [2020] 1 LNS 8 [34] Multazam Development Sdn Bhd v Felda Global Ventures Plantations (M) Sdn Bhd [2020] 11 MLJU 606 [35] CT Indah Construction Sdn Bhd v BHL Gemilang Sdn Bhd [2020] 1 CLJ 75 MY SOPL – SECURITY OF PAYMENT LEGISLATION IN THE MALAYSIAN CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY, MY OBSERVATION…8/15/2019 [UPDATE - 02]: It was reported by the AIAC that CIPAA has overtaken arbitration in the feedstock of cases in the construction law.[1] Notwithstanding its popularity, the nature of CIPAA has invited many criticism for the obvious lacked of ‘refined-justice’, warrants for a much delayed reform.[2] Such ‘conundrum’ pushed the boundary of CIPAA adjudication, even season adjudicators are confused as to the application of the law in adjudication, thus this paper attempt to address the ‘latest development’ as per 2021, in the application of the law in adjudication. -------------------------------------------- [1] AIAC Annual Report 2019-2020: Oct 2021, 200 reported cases in the HC; 2020, 100 reported cases in the HC; 537 cases registered with the AIAC. [2] <https://www.aiac.world/events/398/PUBLIC-FORUM:-REFORMS-TO-THE-CONSTRUCTION-INDUSTRY-PAYMENT-AND-ADJUDICATION-ACT-2012>, accessed 22 Mar 2022 Following the birth of a statutory adjudication scheme in the UK under the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996[i] (the “1996 UK Act”), on 1 June 2015, many countries within the commonwealth had taken the similar bold steps to enact the similar Security of Payment Legislation SOPL within their own legislation. Fundamentally SOPL, as its name suggested, is a piece of legislation to ensure that payment to the contractors are secured as payment is a fundamental ‘life-line’ to any business of construction, without it the entire machinery of construction will collapse and such will create detrimental ripple effects to both the downstream and upstream of the economy. In a nutshell, the theory behind SOPL is to ‘pay first, argue later’ based on ‘rough justice’ with legally binding decision that has no ‘finality’ thus providing only temporal relief.