The Modern Maze of Data Centers: Navigating Through Types, Risks, and StandardsIn the digital age, the backbone of our internet, cloud services, and essentially the entire online ecosystem rests on the shoulders of data Centres. These technological fortresses not only store, process, and distribute vast amounts of data but also ensure that this information is readily available and secure. Understanding the various facets of data Centres, from their types and associated risks to the standards governing them, is essential for businesses and tech enthusiasts alike. Let's delve into the intricate world of data Centres. The Five Pillars of Data Centres1. Enterprise Data Centres: Owned and operated by businesses, these data Centres are the traditional powerhouses of the corporate IT world. They house critical computer systems and components, including backup power supplies, ensuring the smooth operation of business processes. 2. Co-location (Colo) Data Centres: In the co-location model, a third party provides the physical space and necessary facilities, while the customer brings in their servers and storage solutions. This setup offers businesses flexibility and scalability without the high initial investment of building their own data Centre. 3. Cloud Data Centres: Cloud data Centres are operated by Cloud Service Providers (CSPs) and offer computing resources over the internet. They support various service models like Software as a Service (SaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), underpinned by stringent Service Level Agreements (SLAs). 4. Hyperscale Data Centres: These are the behemoths of the data Centre world, owned by tech giants such as Google and Amazon. Hyperscale data Centres support massive scale operations, with at least 500 cabinets and occupying spaces of 10,000 square feet or more. 5. Edge Data Centres: Located close to the edge of networks, these data Centres are designed to deliver content with minimal latency. They are smaller but crucial for applications requiring quick data processing and delivery. Navigating Through Downtime and Risks Data Centre downtime is the bane of the digital world, leading to significant financial losses and operational disruptions. Downtime can result from power failures, human error, and various other factors. The average cost of downtime can be calculated based on the revenue lost during these periods, emphasizing the critical nature of data Centre reliability. Risks to data Centres are twofold: natural disasters like floods, and human-induced errors or vandalism. Among these, human error and equipment failures are the most significant contributors to data Centre outages. Types of Rating, 4 types namely:

Downtime means loss of ability for the DC due to power loss, surge and human error. Calculation of value loss for downtime: Average costs of downtime = Revenue loss due to downtime in $ / 8760 hr per year, where 8760 = 24 x 365 Standards and Selection: The Blueprint of ReliabilityThe reliability and efficiency of data Centres are governed by a mix of accredited and non-accredited standards such as ANSI/TIA 942, EN 50600, and the guidelines from the Uptime Institute. These standards outline specifications for everything from electrical setups and earthing to fire protection and environmental controls. When selecting a site for a data Centre, factors such as power availability, reliability, scalability, and operational costs are paramount. Future-proofing the selection means considering potential natural and man-made hazards, local infrastructure, and compliance with both local and international standards. The Future Is NowAs we continue to demand more from our digital services, the role of data Centres will only grow in importance. Understanding the different types of data Centres, the risks they face, and the standards that guide their operation is crucial for anyone involved in the tech industry, from executives and IT professionals to entrepreneurs.

In navigating the complex landscape of data Centres, it's clear that while the challenges are significant, the opportunities for innovation and efficiency are boundless. As we march forward into an increasingly digital future, the evolution of data Centres will undoubtedly be at the forefront of technological advancement.

0 Comments

MY OPINION: SIGNING THE CCC, EQUALS ‘DEATH SENTENCE’?Presumption of Innocent

The ‘buck’ don’t actually stop with the Architect, in any legal position, where the ‘presumption of innocence’ must always be upheld, unless proven guilty, in a situation of liability under the Street Drainage and Building Act 1974 (‘SDBA’), the ‘parent Act’ for the Uniform Building By-Laws (‘UBBL’). Statutory Declaration The provision of the issuance of the Certificate of Completion and Compliance (‘CCC’)[1], is by virtue of a ‘statutory declaration’ that prescribed: “I/We hereby issue the Certificate of Completion and Compliance for the […] after having satisfied that it has been completed in accordance with approved plan […]” and “I/we certify that I/We have supervised the erection and completion of the […] and that to the best of my/our knowledge and belief such work is in accordance with the building and structural plans and that I/we accept full responsibility for those portions for which […] are respectively concerned with.”[2] What is a ‘statutory declaration’? Can such a declaration in the CCC can be construed as a ‘statutory declaration’? Statutory Declaration Act 1960 provided the definition of ‘statutory declaration’ as a formal statement made by an individual i.e. an Architect, required by the regulation, i.e. UBBL and it will be signed in the presence of a solicitor, commissioner of oath or a notary public, in this case, it ought to have been such. Such statements are generally satisfy legal requirements as well as regulations when no physical evidence is available at that point of time, hence, such declaration is required to be truthful and accurate.[3] Thus, in all purpose, such ‘declaration’ as provided in the CCC mirrored the definition of ‘statutory declaration’ as in Statutory Declaration Act 1960, with the exception that it does not require the presence of a solicitor, commissioner of oath or a notary public, because as an Architect, one is presumably a professional registered with the relevant board, in this case, the Board of Architects Malaysia (‘LAM’), a government statutory body. Such position mirrors the decision as in Dolomite Properties v Ang Chai Kian [2018][4], Wan Adli v Gema Mantap Sdn Bhd [2020][5] and The Haven v Jason Ong Kian Heng [2018][6] What happened if such ‘statutory declaration’ is breached? Under the same Act, the declarant, if found guilty, can be charged under criminal.[7] Thus, if there is an element of fraud in such undertaking, the ‘buck’ don’t actually stop with the Architect. It has to be opened up for criminal investigation, as the undertaking of CCC is annexed to the entire matrixes of undertaking of the 21 forms of ‘Borang-G’. The liability falls within the person who actually certify the relevant ‘Borang-G’, not necessary the Architect, under the principle of ‘presumption of innocence’. In the case of fraud, the threshold of proof is even higher, i.e. beyond reasonable doubt.[8] Saying such, new professionals such as Inspector of Works (‘IOW’) and Certified Construction Managers (‘CCM’), whom are required to sign on the ‘Borang-G’ are equally responsible. Prima Facie Unless Disputed In Kembang Serantau Sdn Bhd v Perbadanan Putrajaya [2022][9], the issue on finality of the CMGD, liked any certificate issued by the Architect, is only prima facie that such work has been completed unless disputed. In the same vein Kembang Serantau holds that a certificate just liked a CCC, which is also a certificate, is nothing more than an Architect’s opinion or prima facie that such work has been completed according to the approved plan, unless disputed. Interestingly, CJ Tengku Maimun observed, the CCC as a legal requirement imposed by law (statutory undertakings via a declaration) which in turn issued upon the developer complying with all the regulatory laws such as the SDBA and the UBBL, accords protection to the purchaser who would be assured that the relevant authorities have approved the construction, cannot be said (to be the same) in respect of the CPC (or any other certificates issued by the Architect) or any such document not amounting to CCC.[10] Apparently the CJ has upheld the sanctity of the CCC above any other contractual certificates, short of saying it is absolute and final as in Wan Adli’s case the LA are entitled to reject any improperly issued CCC. Similarly, in Shabiru (1990) Sdn Bhd v Goh Aik Chin [2019][11], issuance of CCC does not mean that the Architect must have complied with all other contractual and tort obligations. In other word it is not absolute, i.e. finality, as it can be disputed. Board of Engineers Malaysia (‘BEM’) shares the view that PSP are obliged to obtain endorsement for all the 21 Borang G by respective parties to hold these stakeholders accountable. Similarly, BEM also view that by so doing, one can go after the actual person responsible for certain shortcomings or failures, of which PSP would be responsible for failing to check for fraudulent in the Borang-G submission which is not onerous.[12] In the same journal, BEM is aware that the CCC is merely an enhancement of the contract administration role of the PSP and went as far as to say, BEM actually ‘adjudicate’ its members for the shortcomings of ‘procedural’ and fraud. Negligent Versus Fraudulent This is consistent with the findings of Jawead Allah Rakha & 176 ors v Prinsiptek (M) Sdn Bhd [2021][13], where the court rely on the Board to formulate its decision. This however is not a test case for the Board to decide on matter of fraudulent and criminal, but negligence instead, which many instances criminal act is extra jurisdictional beyond the scope of the Board, requiring curial intervention. Waiver In the similar note, a CCC issued can only be disputed, specific to the transgression of the UBBL within the narrow ambit provided by the SDBA and such is affirmed in Aini Ismail & Ors v OSK Properties Sdn Bhd & Ors [2017][14]. Where a waiver is granted i.e. submission of amendment plans or the issue is not pleaded, this cannot be a transgression. As to the question of whether an ‘amendment drawings’ necessitated to be submitted to the local authority (‘LA’) prior to issuance of the CCC? Undoubtedly, it is vested upon the pleasure of the LA[15] as demonstrated in Lembaga Jurutera Malaysia (BEM) v Leong Pui Kun [2008][16], the effects of waiver of a requirement under the UBBL, i.e. submission of the structural calculation, eventually lifted the liability of the Engineer of any wrongdoing on his part even though the ‘link way bridge’ has collapsed. Thus, it is difficult to say the ‘buck’ stop with the Architect when he is allowed to submit his CCC, even when the work on site does not necessarily reflect the approved drawings as accepted by the LA under the provision of UBBL 11. Penalty One must realise that CCC issued negligently and fraudulently are entirely different things governed by different aspects of law. Penalty meted out by the Board range from just a letter of reprimand, fines, suspension and strike off from the roll. However, there arise an argument that the Board is not the right forum to deal with matter affecting the livelihood of a person, guaranteed by the Constitution of the Land.[17] Having said that the transgression of the UBBL such as fraudulently acquired CCC[18] is within the narrow ambit of the SDBA, the maxim ‘lex specialis derogat legi generali’[19] prescribed in the event of transgression the SDBA takes precedent. Thus, only penalties such as fine not exceeding RM 250,000 or to imprisonment not exceeding 10 years or to both can only be meted out by the courts under SDBA. Void Then, the issue with the negligently or fraudulently issued CCC, void ‘ab initio’? ‘There are no provisions in statute or under any UBBL which cater for the invalidation of a CCC issued by a PSP. While a PSP may be penalised for issuing a CCC in contravention of statutory requirements the CCC issued however remains intact.’[20] If we construe the submission of the Building Plan to the LA as a ‘contract’ between the PSP and the LA, a negligently or fraudulently issued certificate, cannot render the ‘contract’ illegal, as such the law on voiding the CCC remains a lacuna. Cause of Action Case law demonstrated that prosecution against an Architect required prima facie evidence of fraud[21] i.e. illegally issued CCC despite the fact that the LA had withheld such issuance[22] and it is a fascinating fact to note that LA should not have intervened in the issuance of the CCC by the Architect but the SDBA allows such to happen. In reality some LA went to the extent of issuing ‘letter of no objection’ to only allow CCC to be submitted for record. In Dua Residency Management Corp v Edisi Utama [2021][23] HCJ Lim Chong Fong held the view as in KL Eco City v Tuck Sin Engineering & Construction, the responsibility for the failure of any building would prima facie lie with the qualified person (PSP) where the SDBA and the UBBL should not arbitrarily be interpreted to impose statutory duty upon the developer, thus a breach of the UBBL would give rise to a private action.[24] Conclusion In my view, saying the ‘buck’ should automatically falls with the Architect, when something goes wrong, is irresponsible and such an act actually caused anxiety among Professionals, be it Architects or Engineers as these stakeholders are generally the PSP. The rules of law such as the ‘presumption of innocence’ must be upheld, as implied throughout BEM’s article mentioned above, as a response to an article, currently a subject of dispute.[25] Therefore, it is entirely irresponsible to say, once, the Architect took the ‘statutory declaration’ as in the CCC, he has signed his ‘death sentence’. ----------------------------------------- [1] UBBL 25(A) [2] Lee Shy Tsong v Amprojek Construction [2018] 1 LNS 2088 [3] < https://www.paulhypepage.my/corporate-compliance-in-malaysia-statutory-declaration/>, access 1 Sept 2022. [4] 1 LNS 1900 [5] MLJU 2428 [6] 1 LNS 1409 [7] [n.1] [8]<https://cccd.utar.edu.my/documents/Burden_and_Standard_of_Proof_in_Malaysian_Law_of_Evidence_compressed.pdf>, accessed 1 Sept 2022. [9] 9 MLJ [10] Kanesh on Local Government Laws, (2022 CLJ), v.3,p.240: PJD Regency v Tribunal Tuntutan Pembeli Rumah [2021] 2 CLJ 441 [11] 1 LNS 1380 [12] BEM, ‘Response by the Board of Engineers, Malaysia’ (2019 IEM), v.78 Ir p.72. [13] 1 LNS 396 [14] MLRHU 57 [15] UBBL 11. [16] 6 CLJ 93 [17] Article 5 – Right to life and personal liberty, Constitution of the Federal of Malaysia [18] s.70(27)SDBA [19] Specific law supersede general law. [20] Tan Siew Hong v. Mohd Azli Abdul Hamid & Ors And Other Cases [21] <http://home.sundrarajoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/CONSEQUENCES-AND-FLAWS-TO-THE-CERTIFICATE-OF-COMPLETION-AND-COMPLIANCE-COMPARATIVE-ANALYSIS-WITH-PROPOSED-SOLUTIONS-1.pdf>, accessed 8 Sep 2022. [22] Pendakwa Raya v Chew Weng Leong [2015] MLJU 1238 [23] 1 LNS 74 [24] Kanesh on Local Government Laws, (2022 CLJ), v.3,1.2,p.7 [25] Sundra Rajoo v PAM [WA-23CY-61-10/2021] RECOUPMENT OF UNPAID ARCHITECTURE FEE ARISING FROM TERMINATIONThere are a number of concerns in providing architectural services. Among them, termination of project, leading to termination of services and ultimately, non-payment of fee. Here, we look at these issues.

One has to bear in mind that the Board of Architects Malaysia (LAM) was only empowered to hear and determine disputes relating to professional misconduct and not any disputes between the architect and its client.[1] Thus, the court will find that there is no implication in law that a service of an architect will be automatically terminated upon the discontinuation or termination of a project where the architect has been legally appointed.[2] In the same vein, the said developer must unambiguously state if it intends to terminate the service of the architect and pay the outstanding fee owed to him prior to any issuance of letter of release.[3] On the issue of non-payment of fee, CIPAA has provided a quick avenue for architects to reclaim its fee, on the basis of temporary finality under the service contract.[4] The very tactical maneuvering by defending counsel is to challenge the jurisdiction of the Adjudicator that he has no jurisdiction to hear the case in view that there is no contract between the client and the architect. It is common practice that architects may had proceeded with works without a ‘proper appointment’, i.e. a verbal-contract. Therefore, it is also common for LAM to request a copy of the ‘memorandum of agreement’ from the architect to establish locus-standi of hearing the case. In absence, the court has provided guidance that a contract exist when there is an acceptance by conduct, i.e. by signing on the ‘submission-drawings’ or even sketch-plan, even to an extend of responding to an email.[5] These, considered written-contract, enforceable unless otherwise there is a contention of misrepresentation. As to the quantum of fee, in contrast to the claim by PAM that the scale of minimum fee SOMF is in placed to protect the client and the public, failing non-compliance may risked project delivery to be sub-standard.[6] Unfortunately, that is not the way the court perceived and the court has also gone an ‘extra-mile’ to say that “unexpected in a case where in a competitive market one has to try to anchor in the work and secure the project [by not complying with the SOMF]”[7], whereupon a term in the contract cannot be changed merely by reason of a termination of services; an agreement that does not conform to SOMF, i.e. on lump-sum, shall not be based upon SOMF as its basis of claim; as SOMF is only binding to the architect but not the contracting party.[8] Concluding, while the Malaysia Productivity Corporation (MPC) may justify there is no reason to maintain price-fixing by professional bodies quoting cases from the US instead of the common law[9], recouping of unpaid fee arising from termination can be a delicate act of balancing between risks, time, goodwill and sheer persistency. The question is, unlike CIPAA, architect cannot exercise a lien so easily over its deliverables and the only sole mechanism to hold ‘ransom’ of ‘unkind-client’ is via its certificates and letter of release. So, don’t force the architect to take the ‘extreme-measure’ as he has still bills and salary to pay, just like you and me. ----------------------------------------------- [1] Arkitek Tenggara Sdn Bhd v Mid Valley City Sdn Bhd [2007] 5 MLJ 697 [2] Ibid [3] Opcit [4] Martego Sdn Bhd v Arkitek Meor & Chew Sdn Bhd Civil Appeal No 02(f)-3-01/2018(W) [5] GC Architect v DeChoice Sdn Bhd and Lim Kim Heng Civil Appeal No BKI-12B-3/3-2016 [6] Berita Arkitek December 2020 [7] Ar. Lim Yoke Tiang v Matrix Concepts (Central) Sdn Bhd [2020] 1 LNS 35 (CA): p.15.L.[27] [8] <http://www.davidyek.com/critics/can-the-architect-claim-scale-of-maximum-fee-in-the-face-of-termination> [9] <http://www.mpc.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Regulatory-Review-Price-Fixing-for-Professionals-in-Building-Constructions-November-2014.pdf>, access 3 May 2021 A QUALITY STANDARD APPLIED TO ALL CONSTRUCTION WORK?Defect is such a ‘dirty’ word. Home owners shun it. Contractors hate it. Unfortunately, government agencies and Architects will have to deal with it. Occasionally, defects are the source of incomes to third-parties, such as, claim-consultants (some are lawyers); forensic-experts; and defect-rectification contractors, alongside the entire ‘eco-system’ that support the ‘defect-rectification’ industries from the tribunals to the supplier of materials and ‘quality-assessment’ course/standard provider. In reality, a discomfort for owners, are indeed ‘cari-makan’ tools/opportunity to others and I said it out loud on the basis that any ‘services’ that can solve people’s problem is a good industry with ‘profitability’.

So, the other issue related to defects are, what standards to apply? How to determine a defect is a defect? Who to determine what? When can mitigating action be taken? Why such measure be taken? Answering such is a ‘monumental efforts’ resulted in many man-hours and public-funded spending aka taskforce, committee, working-group and so-forth both at institutional and governmental level. However, this write-up only limit to a question, is CIS-7 a standard to be adopted generally to the construction industry? Foremost, CIS-7[1] is a standard adopted by the CIDB[2], initially borrowed from Singapore’s CONQUAS[3] system of quality assessment in the construction industry. It has since undergone various ‘metamorphosis’ and had been once dished out as the ‘knight in shimmering armour’ to be mandated by the Work Ministry in 2020[4], that has yet to see the ‘light of the day’. Unfortunately, CIS-7 of QLASSIC[5] is not an acceptable ‘standalone’ industrial standards because they are quality assessment-standards, optional only if the parties decided to adopt when they go into a building contract. Why it cannot be made, mandatory? Regardless if a building costs ten of thousands or millions, defects are generically applied and occur without any constraint of costs and value. However, such costs and values can determine if the quality of works can meet a certain performance standard, thus evaluative tools such as CIS-7 of QLASSIC and CONQUAS are designed for such, rendered these optional, not mandatory. As it stands now, CIS-7 of QLASSIC cannot be a subjected standards adopted in the court of law to be applied nationwide.[6] What if it is to be made mandatory? Such may have legal-repercussion throughout. Foremost, the UBBL only warrants the suitability of materials and workmanship[7] with the ultimate question of what is defined as suitability? Whose standards? Under The Street, Drainage & Building Act 1974 (amended 2007) SDBA, the “principal submitting person” means a qualified person who submits building plans to the local authority for approval in accordance with this Act.[8] Meaning he is the principal submitting person to undertake the statutory responsibility, thus the quality standards must be in accordance to his specifications, not CIS-7 of QLASSIC. So, how on earth can CIDB overrides the SDBA 2007? Even causation in tort needs proof and that is not going to be easy by just relying on res ipsa loquitur.[9] Construction law goes into the extent of ‘risk-allocation’ as to latent and patent defects that cast no meaning to the general public. The voluminous standards by the BSI, AS, Euro-Code and our MS, governing materials, tools, applications and so forth may only make sense to the professionals and are constantly changing. So, where are we? PAM[10] has objected to this application of CIS-7 of QLASSIC as national-standard.[11] Knowing how things move within the ‘chain of deliveries’ architects will be ‘side-lined’, as reported.[12] It will comes a time when a CIDB QLASSIC Assessor will be dictating to the Architects as to ‘which qualities prevailed’, while running-free if the building collapsed.[13] Do Architects want this to be the reality? ---------------------------------------------- [1] CIS-7:2014 Quality Assessment System for Building Construction Works [2] Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) [3] Construction Quality Assessment System (CONQUAS) [4] <https://www.nst.com.my/business/2019/03/471636/works-ministry-make-qlassic-certification-mandatory-2020-onwards> [5] Quality Assessment System in Construction (QLASSIC) [6] <http://rehdainstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Mr.-Mohammad-Faizal-Abdul-Hamid.pdf>: the use of any standards is voluntary & compliance with this document does not in itself confer immunity from legal and contractual obligations. [7] S.53 UBBL 1984 [8] S.3(e) SDBA 2007 [9] Latin maxim, meaning ‘let the thing (evidence) speaks for itself’, in law of evidence. [10] Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia (PAM) [11] Berita Arkitek BA (Feb 2021): PAM’s Feedback on the Draft CIS 7:2020 [12] Berita Arkitek BA (Feb 2021): Report of PAM Representatives on Government Standing Committees, Councils and Boards (Jawatankuasa Teknikal Standard Industri Pembinaan (CIS7) QLASSIC) by Ar. Steven Thang [13] S.258 UBBL 1984 OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH IN THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY (OSHCIM) ANOTHER CONSTRUCTION DESIGN MANAGEMENT (CDM) IN DISGUISE?I am re-writing this article on Occupational Safety & Health in Construction Industry Management (OSHCIM), after having much clarity as to where it begins. OSHCIM is just another hybrid of Construction Design Management (CDM) UK and Design for Safety (DFS) Singapore and a direct adoption of Construction soon to be enacted, will be another matter to be dealt with by the construction industry. It adds up additional cost, 2% out of the developer's pocket, well much decent compared to the architect's fee.

So to speak, this new regulations will significantly shift the risks upstream back to the architect. Blatantly erred, to say that architect like it or not, has to owned up to their design liabilities and what has this regulation imposed are not much the different. Yet, they forgot negligence has to be proven. As this legislation that foresee to be gazetted 6 months down the road, Singapore took 6 years, imposed a self-declaration of design liabilities, that they called risks, voluntarily into a document called risk-register. This document will be expended as it snowballs downstream right to the occupier. The question remain to be seen is, how easy would the occupier take this document to find faults with each and every party in the delivery system, since it is already a self-confessed 'sin'? This document has no privileges in evidence law. One may say, just 'simply' do it and make it as ambiguous as possible? Nay, CIDB will imposed a self-regulatory mechanism with a paid consultant monitoring this processes, full time at your expanse via the weekly OSHCIM meeting. They will not provide solutions to the problem as they would not want a piece of the design liabilities from the architect, they are basically checker to make sure that the architect crosses the T n dots the I, in their self-imposed declarations of liabilities. Least to say, they imposed strict rules for the architect to owned up to their liabilities under the spirit of if you fail to plan you should first plan to fail, in that way you will minimize risks downstream. In reality the architect's risk has not reduced an ounce but has increased significantly as it includes other risks as well particularly from the builders. It becomes clear that CIDB via this mechanism manage to pass the buck of their conundrum upstream to the architect in a subtle way as the dialogue now imposes that architect is responsible for Contractor's safety on site and the ministry buys it! Given the scenario of below cost acceptable tender sum is taken by foreign contractors and 0.5% dirt cheap architectural fees were forced through our throats, now, plaguing the profession and the construction industry at large, do the architects want to support it? A PAGE FROM Construction Design Management (CDM) UK: To critically-evaluate the ‘health and safety’ duties imposed upon contractor, one has to consider what are the common-law and Construction Design Management Regulations 2015 (CDM2015) enforced in the UK? How would Employer’s positions be different if Employer acted as both principal-designer and project-manager? Historically, Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 (1974 Act) empowers Construction Design Management (CDM) – Regulation 1994 (CDM1994)[1]; with employers’ duty ensuring, health, safety and welfare at-work, applied to the other-persons[2]; without-risk[3]. Prior to 1974Act, workers-welfare was governed by Factories Act1961, applied in the construction-industry. Failure to integrate CDM-regulations into ‘non-domestic’[4] construction-practices[5] are criminal-offences[6]; HSE-inspectors empowered to inspects/take documented-copy/samples[7]. CDM has since been improved/updated from CDM1994, CDM2007 to the current, CDM2015; promotes identification-elimination of Health and Safety risks from ‘project-lifecycle’ commencing, ‘pre-construction-phase’, right-up to post-occupational, i.e. building-decommissioning; with different Health and Safety role/responsibility vested-upon different stakeholders, i.e. principal-designer/Architect/Engineer/Client[8] at ‘pre-construction-phase’[9]; principal-contractor at ‘construction-phase’[10]; QS/Procurement-Managers at ‘procurement’ right-up to Maintenance-managers/End-users at ‘post-occupational’. CDM2015 required the HS-File to be kept, maintained, updated and transferred from one stakeholders to another, throughout the project-lifecycle.[11] In addition, it will be necessary to ensure that right-people appointed-early, have time-to-review materials and involved in setting-up processes.[12] If none-appointed, client obliged to-carry out these-duties.[13] Rationales are, client is key-role-stakeholder[14], has overall-control; can properly-managed at all-stages[15]; if insufficient-knowledge/resources, he employs designer/competent-people to-assist[16]; managing-project, i.e. ‘suitable-project-management’. “Suitability”, means work without-risk[17]. He makes-available ‘pre-construction information’ i.e. drawings, Health and Safety-file, surveys, to designer/contractor, ensuring phase-plan completion, where designer/contractor complies with duties, allocation of sufficient-‘time/resources’, continue ‘maintained/reviewed’ Health and Safety risks[18]; and future-appointments[19]; provide facilities such-as sanitary, washing, drinking-water, changing-rooms and rest-facilities.[20] Traditionally, CDM2007 was meant to stamp-out deficiencies arising from tight-budget, care-less site-cultural/attitudes, and motivates promotion of safe-place on construction-work. A stricter-legislation would influence construction-workers be more-observant to Health and Safety risks. Thus, common-law on man-slaughter since codified, as Corporate-Manslaughter and Homicide Act2007 (The-Act), to address weaknesses of ‘identification-principle’ formerly, only “hands-on” directors were-convicted, instead of ‘main-culprits’.[21] The-Act determines corporate-liability by judging management-adequacy across organisation. Penalties imposed, unlimited-fine; remedial-order; publicity-order; compensation-order; prosecution-costs order; and victim-surcharge, with sentencing not-less than £500,000. However, CDM2007, issues with interpretation, bureaucracy, and onerous-competency resulted lack-of-coordination in preconstruction-phase; coordinators’ late-appointment, lack of resources and failure to-include coordinators into design-team. Changes/amendment to CDM2007 were logical. CDM2015 devised to address Health and Safety concerns, previously vested-upon ‘competent-person’, now to designers/client whom are influential from the outset; reduce overlapping-trend of multiple-accreditations, by removal of ‘Approved-Code-of-Practice’; embedding CDM2015 into smaller-projects, where majority accidents-occur, by requiring ‘construction-phase plan’. Construction-industry stakeholders have to be aware of duties prescribed to them; when project becomes notifiable to the relevant-authority, i.e. notice be-given, in-writing to HSE prior to construction. Moreover, CDM2015, although instituted significant-additions, has weaknesses i.e. ‘domestic-client’ often unaware of such-duties by-default, unlikely to be appointed-to contractor/architect; confusion in appointing principal-designer for ‘pre-construction’, and principal-contractor for ‘construction-phase’; domestic-premises are ‘small-timer’ ignorance of CDM, will typically fall-out from the often-changing threshold-notification to HSE[22]; where 1974-Act are oblivious to most domestic-work; adding-up bureaucratic red-tapes, i.e. HS-File cum Health and Safety Coordination-Meeting; differing-opinions to the absent of CDM-Coordinator; for costs-reduction having architect, double-up as principal-designer with additional-burden/responsibilities; if failing to-appoint, client takes-upon himself, such-extra-burden; even if architect willing, it will not be ‘pro-bono’[23]; obscurity of ‘designer’, a contextual-term devoid of any professionally-linked core-competency but merely Health and Safety administrative role; such principal-designer ‘necessary-skills’ in-lieu of CDM2007’s-‘competence’ are mere-semantic; opportune upon others to-provide ‘training-ground’ as ‘cash-cow’; HSE’s-premise, ‘client, most-influential throughout the-project’ will not-change the fact that ‘client is-king’, often CDM worst-offenders[24]; that takes-account client assuming principal-designer has added vested-duties, include those outside CDM-Coordinator’s scope. In Contractor’s positions as principal-designer, its role, focus for Health and Safety issues rather than ‘outsourcing’ it; the definition of “designer”, not-exclusive, can also be client/contractor.[25] The term-“Design”, includes drawings, design-details, specification, generally assumed by Architects, Engineers, Surveyors, others; anyone who specifies/alters design, specifies use of particular-method of work/material; who-specifies building-layout; MAP-Engineers; contractors; and temporary-works engineers, but under CDM2015 designers are ‘unique-position’ for-purpose of risks-reduction/hazards-identification with responsibilities, not-confined to construction-phase but to-covers Health and Safety issues, post-completion. Contractor will resumes Health and Safety duties[26], to ensures his-awareness(as Client, too), i.e. know client’s-duty, the work-amount; risks-elimination, i.e. take-account of general-principle of prevention[27], pre-construction information, in place, eliminate-foreseeable risks[28], maintain/cleaning the-structure, alongside cost, fitness-for-purpose, aesthetics and environmental impact[29], ensuring other-designers compliance[30], cooperation[31], liaise with principal-contractor[32]; providing design-information[33], delivered-effectively; includes providing other “significant-risks” information; to identify risks-arising from design-integration; with design-reviews scope made-available. Designers do-not have-to, take-account of, unforeseeable-hazards and risks; possible future-uses of structures; to-specify construction-methods; to-exercise any Health and Safety management function over contractors. Principal-designer is not by-qualification but by safety-influences, i.e. in organisational-abilities.[34] Contractor’s positions as project-manager(PM), under CDM2015, is obliged-to resume principal-contractor’s role covering ‘construction-phase’ under non-domestic, notifiable-project, and to provide relevant-information to HSE, allowing them to monitor projects; accordance to HSE-thresholds[35]; with additional-information[36], i.e. planned-commencement/duration; time-allocation[37]; workers-number(max); and CDM-compliance declaration.[38] Principal-contractor[39] is person-appointed with specific-duties[40], in influencing Health and Safety management in ‘construction-phase’, i.e. particular-work on ‘design-technical-organisational’[41], ‘general-prevention’ of risks[42], manage other-contractors[43]; consult-engage with workers[44] via, site-induction[45]; unauthorised-access prohibition, facilities[46]; principal-designer liaison[47]; specific-obligations[48], i.e. competent-workers[49]; work-supervision[50]; information to workers[51]; unauthorised-access prevention[52]; welfare-facilities[53]. Whereas, ‘construction-phase plan’, “set-out Health and Safety arrangements and site-rules” for dangerous-risks[54]; a ‘living-document’; criteria are relevancy; sufficient-detail; proportionate to project-scale/complexity. Health and Safety File made by principal-designer; kept up-to-date. Concluding, notwithstanding the noble-intention of CDM2015 to document risks-preventions, it is not without its-setbacks; although CDM has been adopted in various-jurisdiction[55]; the same uncertainty-fears permeate among industry-stakeholders. Contractor’s position as both principal-designer and PM, are indifference as of the overarching client’s-duty under CDM2015; applied from ‘preconstruction’ to ‘post-construction’ phases. --------------------------------------- [1] Part1.1974Act [2] S.2-3.1974Act [3] S.4.1974Act [4] Regulations make distinction between “domestic”, i.e. work-done on their private-home and “nondomestic”, i.e. work in-connection with furtherance of business [5] Construction-work includes building/engineering-works; retrofitting, renovations, demolition, etc; also include, preparation-planning; pre-fabs assembly; waste-removal; maintenance-repairs; exclude mining and its related-works. Structure is construe as, building, either temporary/permanent-materials; railways; dock-harbour; tunnel-bridge; etc. include formworks/scaffolds. [6] S.20-22.1974Act [7] Health and Safety(Enforcing Authority)Regulations1998 [8] Reg.4 or 8, or in Reg.6.CDM2015:notifibility [9] Via ‘client-brief’ stating, main-function and HS-requirements; time-frame and budget; design-direction with “risks-nature”, relevant HS-standards and maintenance; design-team’s expectations/scope in risk-management; identifying commissioning-arrangements of new-building. [10] Reg.2(1),CDM2015 [11] Schedule-3,CDM2015:document identifies risks encountered/managed/mitigated, with processes/arrangements in-place; site-rules and specific-measures to-mitigate, are required for projects with more-than-one contractor, prepared by principal-designer [12] Reg.8CDM2015 [13] Reg.5(3)-5(4)CDM2015 [14] Part2.1974Act [15] Part4.1974Act [16] Part3.1974Act [17] Reg.4(2)CDM2015 [18] Reg.4(1)-4(3)CDM2015 [19] Reg.4-5CDM2015 [20] Schedule-2CDM2015 [21] P&O European-Ferries[1991]93AppR72 [22] <https://www.shponline.co.uk/legislation-and-guidance/review-cdm-regulations-2015-part-1/>:30-days or 500-person-days to include more than 30-days and have more than 20-workers working simultaneously; or exceed 500-person-days [23] <https://www.shponline.co.uk/legislation-and-guidance/review-cdm-regulations-2015-part-1/>:HSE-Impact-Assessment estimated £23-million saving per-annum is overly-optimistic [24] <https://www.shponline.co.uk/legislation-and-guidance/review-cdm-regulations-2015-part-2/>:83/69 convictions(April-1999 to May-2014)equals 5/annum [25] Reg.2(1),CDM2015 [26] Reg.11-12,CDM2015 [27] Reg.11(2),CDM2015 [28] Reg.11(3),CDM2015 [29] Reg.11(1),CDM2015 [30] Reg.11(4),CDM2015 [31] Reg.11(5),CDM2015 [32] Reg.11(7),CDM2015 [33] Reg.11(6),CDM2015 [34] MWH v Wise[2014]EWHC427(Admin) [35] Reg.6,CDM2015 [36] Covers forwarding-date; site-address; local-authority; brief-description; contact-details of project-team [37] Reg.4(1),CDM2015 [38] Schedule-1,CDM2015 [39] Reg.13-14,CDM2015 [40] Reg.13,CDM2015 [41] Reg.13(1),CDM2015 [42] Reg.13(2),CDM2015 [43] Reg.13(3),CDM2015 [44] Reg.14,CDM2015 [45] HSE:Construction-Information-Sheet(No.59) [46] Schedule-2,CDM2015 [47] Reg.13(5),CDM2015 [48] Reg.15,CDM2015 [49] Reg.15(7),CDM2015 [50] Reg.15(8),CDM2015 [51] Reg.15(9),CDM2015 [52] Reg.15(10),CDM2015 [53] Reg.15(11),CDM2015 [54] Schedule-3CDM2015 [55] Occupational-Safety-and-Health in Construction-Industry(Management)2017(OSHIM):Malaysia; Design-for-Safety:Singapore, <https://www.wshc.sg/wps/PA_IFWSHCInfoStop/DownloadServlet?infoStopYear=2014&infoStopID=IS2010012500120&folder=IS2010012500120&file=DfS_Guidelines_Revised_July2011.pdf> CAN THE ARCHITECT CLAIM SCALE OF ‘MAXIMUM’ FEE IN THE FACE OF TERMINATIONUPDATE: Hardie Development Sdn Bhd. v David Shen I-Tan[1] provided clarity as to the following questions[2]:

The court holds that ‘charging of professional fees by Defendant less or lower than the minimum fees as prescribed by and in breach of the Architects (Scale of Minimum Fees) Rules 1986 does not render the architect’s service contract or contract of engagement with his/her client void or unenforceable so as to deprive the architect of any right to recover his/her fees or remuneration.’ In arriving to such decision, the court hold that:

Applying the principles of law as stated in Co-Operative Central Bank Ltd (In Receivership) v Feyen Development Sdn Bhd[5]; Lori (M) Bhd (Interim Receiver) v Arab-Malaysian Finance Bhd[6]; Asia Television Ltd. & anor v. Viwa Video Sdn. Bhd.[7]; Becca (M) Sdn. Bhd. v. Tang Choong Kuang & anor[8]; with the reasoning of Justice Lee Swee Seng in Matrix Concepts (Central) Sdn. Bhd. v. Ar. Lim Yoke Tiang[9]. In essence, the findings in Matrix Concepts is still the deciding factor and rest assured that such decisions has given the precedent that it is not illegal for architects to charge below the mandatory scale of minimum fee Rules … then the question, why mandatory? ------------------------------------------------------- [1] [2020] MLJU 1103 [2] Hardie [n1] at [25] [3] Hardie [n1] at [96]: cited St. John Shipping Corporation v. Joseph Rank Ltd. [1956] 3 All ER 683 [4] Hardie [n1] at [99]: cited Narraway v. Bolster (1924) Estate Gazette 83 [5] [1995] 3 MLJ 313 (FC) [6] [1999] 3 MLJ 81 (FC) [7] [1984] 2 MLJ 304 [8] [1986] CLJ (Rep) 64 [9] [2018] MLJU 1548 The question of law, whether can the Architect charge below its Scale of Minimum Fee (SOMF) Rules? If so, whether can the Architect claim its fee under SOMF Rules when the letter of appointment (LOA) that has been entered upon does not comply with the SOMF? If so, whether ‘letter of release’ (LOR) was obliged to be released without delay even though the Architect holds a lien over the document pending payment of its fee, when the LOA specified in contrast with the provision of the Architects Rules 1996?

The old case of Seniwisma S & O Akitek Planner v Perusahaan Hiaz Sdn Bhd [1980][1] held that the Architect’s fee was pursued under SOMF but the court was extremely careful in awarding based on SOMF and subsequently set-aside appeal, instead, due to the nexus of facts points toward the approved layout deviates from their proposal, implying that the appellant's layout has not been used as the approved layout. Whereupon the court continues to guide us that Scale of Fee (SOF) without the word minimum is for the purpose of to check recalcitrant consultants who impose exorbitant fees to the public.[2] In the same vein, court is ready to accept the legitimacy of consultant charging below the SOF.[3] As to the question, can the Architect charge below its SOMF Rules, the legal position has always been, ‘yes’ but specifically it remains untested.[4] A recent appeal case of Ar.Lim Yoke Tiang v Matrix Concepts (Central) Sdn Bhd [2020][5], posted the following ratio-decidendi, a term in the contract cannot be changed merely by reason of a termination of services[6]; whereupon an agreement that does not conform to SOMF, i.e. on lump-sum, shall not be based upon SOMF as its basis of claim[7]; as SOMF is only binding to the architect but not the contracting party[8]; whereupon LOA is clear that Letter of Release (LOR) was obliged to be released without delay, maintaining the Architects Rules 1996 on a lien[9] over the documents pending to be paid, has no application[10], when the LOA was prioritised over the Architects Rules 1996. As for this Ar.Lim Yoke Tiang v Matrix Concepts (Central) Sdn Bhd [2020], we have yet to see if LAM actually takes the trouble to sanction the architect for procuring works below the SOMF and as usual, nobody can have access to Board of Architects (LAM)’s proceeding on issues of professional-misconduct, which may have been conducted in an opaque-manner. Concluding, just like the saying “unexpected in a case where in a competitive market one has to try to anchor in the work and secure the project”[11], it is no secret that most Architect has not played by the Architects Rules 1996 in imposing the mandatory SOMF-Rule.[12] The court is ready to accept the reality that SOMF is only binding to the architect but not the contracting party. In response, LAM has since mooted the idea of ‘stakeholder’ to collect fee on behalves of the architects[13], but that has yet to see the light at the end of the tunnel. In a nutshell, court will not make a contract for the parties when there is none, more so, court will not apply ‘extra-contractual’ concepts when there is a contract binding the parties, that include superseding any rules contradicting the true-intention of the parties in contract. ---------------------------------------------- [1] 2 MLJ 37 [2] Mott Macdonald (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd v. Hock Der Realty Sdn Bhd [1996] MLJU 342 [3] Sri Palmar Development & Construction Sdn Bhd V Jurukur Perunding Services Sdn Bhd [2010] 6 MLJ 166 [4] The late Ar. Kington Loo, did mention that there was a test-case on this but it did not survive due to the demise of the architect. [5] 1 LNS 35 (CA) [6] p.14.L.[25] [7] p.15.L.[27] [8] p.16.L.[28] [9] Hughes v Lenny (1839) 5 M. & W. 183: lien to recover its due [10] p.20.L.[40] [11] p.15.L.[27] [12] As per studies carried by PAM [13] <https://lam.gov.my/index.php/latest-news/410-lam-stakeholder-fee-management-system1.html> THE SUPREMACY OF APPROVED-DRAWINGSThis writing is to guide QS, contractors and graduate-architects into understanding the various drawings…

In the profession of an architect, it is common to know that there are various issuance of drawings, originated from his office such as, Schematic-Drawings (sometimes called sketch-drawing), BP-Drawings, Bomba-Drawings, SPA-Drawings, Tender-Drawings, Construction-Drawings, Shop-Drawings and As-built Drawings. What are these exactly, or rather legally? There are three-statutory provisions that make a ‘drawing-legal’, means the architect will have to sign on it declaring, ‘certify that […] are in accordance to the UBBL 1984 and […] accept full responsibility’[1]. One, the Uniform Building Bylaws 1984 (UBBL), the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966 (HDA) and the Contracts Act 1950. The moment the architect submitted his Schematic-Drawings for the consideration of the local authorities, including the fire-departments, these Schematic-Drawings had been elevated to become BP-Drawings and Bomba-Drawings, respectively. Both are construed as a ‘legal-document’ undertakings of liability by the architect to the public (authorities). Collectively, once ‘approved’ it is known as Approved-Drawings. Since it is an undertaking, it has to conform to every terms of the law, failing which the architect is liable for professional-negligence and misconduct, tantamount to criminal charges. That is the degree and gravity of compliance. The Approved-Drawings were to be translated into SPA-Drawings. In essence, it is supposed and legally should be an extract of the Approved-Drawings. In a nutshell, it is supposed to be the Approved-Drawings in manageable sizes to be inserted into the Sales and Purchase Agreement SPA between the Vendor and the House-buyer under the provision of the HDA. Therefore, it has no-further undertakings required by law, i.e. the HDA, thus, architect do not need to sign on it. The same Approved-Drawings were to be expended to include ‘blow-up’ detailing for the contractor to tender and thus, the name Tender-Drawings. As such it is the same Approved-Drawings and any significant changes will rendered the entire tender illegal and voidable-contract, ab-initio. A contract cannot be upheld if the nature of the contract is illegal, i.e. without the Approved-Drawings. On the same note, architect do not need to sign on these drawings. Similarly, when the contractor is appointed, the same Tender-Drawings must now, be elevated to be the Contract-Drawings and Construction-Drawings. Constructing a building with Construction-Drawings and contract-binding with Contract-Drawings that were differed from the Approved-Drawings will end up with colossal of contractual issues, not only to the contractor and employer but the vendor and its purchaser as well. Ultimately, to get strata-title, under the Strata Title Act 1985[2] and Strata Management Act 2013[3], the architect has to undertake that ‘the parcels constructed in accordance to the approved plans’. As-built Drawings that differed from Approved-Drawings are prima-facie of the architect ‘sleeping on the job’. Thus, you don’t need the architect to sign on the Contract-Drawings, As-built drawings and Construction-Drawings. Having said that, there is also something called the ‘Shop-Drawings’, and this ‘creature’ is not meant to be used as Construction-Drawings. Only ‘lazy-architect’ will use ‘shop-drawings’ as construction-drawings. It is also, illegal to append the Architect’s title-block in shop-drawings, simply because, it is not-prepared by him. It is prepared by specialist-contractors, manufacturers and generally, contractors. Why on earth must it contain the architect’s title-block? The correct application of shop-drawings is to be incorporated into the architect’s construction-drawings and not the other way around. Legally, contractor must not build based on drawings not specified as construction-drawings. As such, do you now, see how important is the Approved-Drawings? The only drawings that must be approved, be tendered and be built by it! Nothing else matter… Postscript: Vincent Tan wrote, ‘We found the contractors does not followed As-built drawing. Meaning what was supposed to be installed was not consistent with the As Built. Can the developer come back and say " we will amend the as built drawings" to make it consistent with actual site installation?’... this question required me to write more about ‘As-Built Drawings’. The meaning of ‘As-Built’ is a prima-facie of what has been built on site, itself an evidence if it does not reflect compliance to ‘Approved-Drawings’, it is entirely illegal and caused ripple across the myriad statutory obligations contravening these legislatures from UBBL 1984, HDA1996, STA 1964 to SMA 2013. It is common for the local authority to request the architect to submit ‘As-Built’ prior to CCC inspection, as a short-cut to amendment of Approved-Drawings. This has since rebuked in the ‘Highland Tower’ Case, where the court held that the practice of ‘As-Built’ is liked ‘holding ransom’ against the authorities compelling them to accept the ‘illegality’ wholesale, to make it legal. Thus, such unhealthy practices are still ‘rampant’. So, the answer to Vincent’s question is ‘Yes’ as developer can use ‘As-built’ to be ‘legalized’ by authorities, since they have the rights under UBBL to amend the ‘Approved-Drawings’ to reflect the ‘As-Built’. Thus, the practical use of the ‘As-Built’ is when an architect really needs to know an existing structure to work on it as renovation or makeover. --------------------------------------------------- [1] UBBL 1984, 2nd Sch. Form-A; s.6UBBL1984 [2] S.9(1)(b)(i): certified by professional architect [that] building constructed in accordance with [approved-plans] to which permission was given. [3] S.6(3) SHOULD I SUE MY ARCHITECT OR REPORT TO THE BOARD?Two-occasions provided me inspiration for this writing. One, a situation where an-architect is challenging the-Institute over wrongful-removal on the register; two, a-question from my Graduate-Architect, preparing for her part-III (equivalent to RIBA-PartIII), with regard to disciplinary-action taken for Professional-misconduct. The issue may have been similar but the context is different. If ever, it can be a question in the Professional-Examination for LAM-PartIII, ‘Write a note to explain to your colleague, who has been called upon for disciplinary-action by the Board of Architect LAM, as pertaining to his defence, arising from his negligence act of providing a service under the Act’.

I reckoned that it is a little-unfair to pose such a question, aptly to be answered by a lawyer, but knowing the law is fundamental to the practice as an Architect, as the saying goes, the Architect is worth, not just by his drawing but by his ‘statutory-undertakings’ under the law, similar to that of other professions. The issues here are, whether can the-Board or the-Institute take actions against its member based on its inherent jurisdiction to interfere into its member’s right for livelihood? If so, whether a proper avenue for recourse is accorded to its member to be heard, as the bed-rock of ‘natural-justice’? If so, whether ‘misconduct’ has actually been breached when its member is yet to be found guilty of a crime in the court of competent jurisdiction? Finally, are the members of the committee or council of the-Board or the-Institute have immunity against any-claim by the members? Foremost, the background. The architect is a profession governs by the-Act[1] and such legislation provided for the setting up of the Board[2] to overlook the profession[3] of Architects and by annexure to the criteria of being a Professional-Architect[4] one has also a corporate-member[5] of the institute[6], a ‘social-club’ for learned-society, bearing no-statutory power. Secondly, the Malaysia-law provided for, the constitution[7] as the supreme-law of the land, hereinafter class-A; the-Act, with it provided for its-Rule[8], hereinafter class-B; the-Board’s discretion as in Order[9] and Circulars[10], hereinafter class-C; and the-Institute’s Advisory[11] and Rulings[12], hereinafter class-D. Thirdly, the Professional-liabilities as in professional-negligence and professional-misconduct. One has to bear in mind, professional-negligence does not equal professional-misconduct. Thus, what constitute professional-negligence and professional-misconduct? Can the-Board or the-Institute administer action pertaining to both? Whether can the-Board or the-Institute take actions against its member based on its inherent jurisdiction to interfere into its member’s right for livelihood? Legally, the-Board is the creature created by the-Act[13], within it, stipulated that it can take action against its member[14], only-its member[15], via the disciplinary-committee[16], subject to hearing[17] and right of representation[18], upon the recommendation[19] of the investigation-officer[20]; limited to only defined-misconducts[21]; including the act of ‘search and seizure’[22] by an ‘authorised-officer’[23], except with ‘lawful-authority’[24]; a subject of much-controversy. But when the ‘counter-claim’ was premised on its member’s right for livelihood, it is a ‘whole new-level’ of consideration, beyond the ambit of the-Board. It involves one, the question of conflict of law i.e. class-B versus class-A; two, the question of the ‘right-forum’ to hear the case with regard to an issue of conflict of law i.e. class-B versus class-A, ultimately, answering whether a proper avenue for recourse is accorded to its member to be heard, as the bed-rock of ‘natural-justice’? Foremost, the constituents of the disciplinary-committee go against the fundamental principle of ‘natural-justice’ to be heard in the court of competent jurisdiction. The question, are the constituents of the disciplinary-committee equal to the court of competent jurisdiction, i.e. the High-Court of the country? Whether the disciplinary-committee has the jurisdiction to hear matter pertaining to restriction of a member’s constitutional rights for the preservation of livelihood?[25] Careful reading of the misconducts is generally and mostly related to the matter of criminality, beyond the term of reference by the disciplinary-committee’s jurisdiction. General reading of the-Act, revealed as though the disciplinary-committee has a wide range of jurisdiction to decide upon its member’s fate. But in fact, the disciplinary-committee has only a very narrow jurisdiction. The correct way, is that the disciplinary-committee is to convict its member, only when the member is found guilty by the court of competent jurisdiction. The-Board cannot take actions against its member based on its inherent jurisdiction to interfere into its member’s right for livelihood, without the conviction from the court of competent jurisdiction. With such, there is an apparent conflict of law i.e. class-B versus class-A. With regard to the act of ‘search and seizure’ that can only be made lawful, by making a ‘police-report’, obtaining the relevant-warrant, prior to the act of ‘search and seizure’. Imagine if you have a situation of a ‘trigger-happy’ enforcing-officer, by each and every trade or professions, competing with the rest of the ‘law-enforcing’ personnel in the country, wouldn’t we revisit the era of the wild-wild west? Even ‘law-enforcing’ personnel requires a warrant to ‘search and seizure’. So, in reality, it is a provision good in theory, lousy in application. The-Institute with only, class-D jurisdiction, has no jurisdiction on this area. If so, whether a proper avenue for recourse is accorded to its member to be heard, as the bed-rock of ‘natural-justice’? The correct forum must commence in the court of competent jurisdiction, not the disciplinary-committee. The disciplinary-committee should under the recommendation of the investigation-officer pursue legal proceeding in the court of competent jurisdiction. Thereupon, conviction, shall the disciplinary-committee take remedial-action against the member. Whether ‘misconduct’ has actually been breached when its member is yet to be found guilty of a crime in the court of competent jurisdiction? Thus, in the same vein, the short-answer is no.[26] Another matter that is unusual is that appeal is only available via the appeal-board[27] only on a narrow matter pertaining to refusal or registration[28] and removal of registration[29]; taking into consideration that these matters interfere into its member’s right for livelihood; warrant that the appeal-board to be presided over by a High-Court Judge[30]. It means to say, any other matter not falling within these refusal or registration[31] and removal of registration[32] are not subject to appeal? As such, contravening ‘natural-justice’? Any difference if the matter of professional-misconduct be heard in the High-Court instead of the disciplinary-committee as it involves interference into its member’s right for livelihood, where the options of further appeal to the Appeal-Court and Federal-Court are available? The drafter of this Act is obviously aware of the gravity it involves and the limitation as to the jurisdiction of the disciplinary-committee. Finally, are the members of the committee or council of the-Board or the-Institute have immunity against any-claim by the members? Public-servant is accorded immunity against any cross-claims arising from negligence[33]. So, the question is, are the-Board and the disciplinary-committee, public-servants? Public services shall consist of the Federal and State General Public Service, the Joint Public Services, the Education Service, the Judiciary and the Legal Service and the Armed Forces.[34] For all intents and purpose, Statutory Bodies and the Local Authorities are also considered as parts of the Public Services. This is because both these autonomous bodies resemble the Public Services in many respects since they adopt the procedures of the Public Services pertaining to appointments, terms and conditions of service and the remuneration system.[35] Therefore, the-Board is a Statutory Bodies, its constituents[36] including that of the disciplinary-committee can be construed as public-servants, enjoying immunity in the context of ‘good-faith’[37]. However, that cannot be applied to members or councils of the-Institute, as they can sue and be sued, collectively and individually. However, a point has to be taken of the inherent nature of the ‘possibility of bias’ on account of the members of the-Board, the-Institute and the-disciplinary-committee, as they are appointed among the peers of practising professionals, whom by strictly to the law, are also ‘competitors’ in some cases, serving the same clients whom are limited in the industry and not from members of the public-servant whom are answerable to only the government. This is a domain for challenge in a sense of mala-fide. Concluding, what constitute professional-negligence and professional-misconduct? Can the-Board or the-Institute administer action pertaining to both? Professional-negligence, as in tort-liability has to be held by the court, not the-Board nor the-Institute. Whereas, professional-misconduct, as outlined by the-Act are illicit-commissions[38]; non-disclosure of conflict of interest[39], fraud/misrepresentation[40], any act of disgrace[41], non-compliance to the-Act[42], as to conditions of registration[43], procuring under fraudulent misrepresentation[44], concealing of facts to the disciplinary-committee[45], contravention of restriction[46], causes sufferings prior-registration[47], or post-registration[48], criminal-conviction[49], withdrawal of qualifications[50], unsound-mind[51] and bankruptcy[52] or incapacity[53]. These have nothing to do with professional-negligence. So, technically unsatisfied clients should not complaint to the-Board on matters of professional-negligence. Instead, they should just sue the architect in the court of competent jurisdiction. The-Board should only administer action pertaining to professional-misconduct, upon the conviction of the court. Whereas the-institute can only administer action upon the conviction of the-Board. Postscript: If the question of law is with regard to the matter of the-Institute alone, as a ‘social-club’ there is very little statutory-jurisdiction on the matter of professional-misconduct, especially so with the existence of the-Board. The-Institute shall not eclipse the-Board. -------------------------------------------------------------- [1] Architects Act 1963 (Amended 2015) [2] Board of Architect Malaysia (LAM) [3] S.4(1) Architects Act 1963 [4] Licensed to practice architecture, carries the title Ar., with post-nominal P.Arch, ALAM. [5] Being Associate of Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia APAM [6] Institute of Architects Malaysia (PAM) [7] The Federal Constitution of Malaysia 1957 [8] Architect Rules 1996 (Amended 2015) [9] LAM Disciplinary-Order [10] LAM-Circular [11] PAM-Advisory [12] As in PAM Arbitration-Rules and the sort [13] S.3(1) Architects Act 1963 [14] S.4(1)(c) Architects Act 1963 [15] S.7 Architects Act 1963 [16] S.15A(1)(b) Architects Act 1963 [17] S.6(a)(i) Architects Act 1963 [18] S.5(a)(ii) Architects Act 1963 [19] S.15A(5) Architects Act 1963 [20] S.15A(1)(a) Architects Act 1963 [21] S.15A(2) Architects Act 1963 [22] S.34B Architects Act 1963 [23] S.34B(1) Architects Act 1963 [24] S.34B(5) Architects Act 1963 [25] Article 5(1) Federal Constitution of Malaysia 1957 [26] Woolmington v DPP [1935] UKHL 1: presumption of innocence [27] S.28(2) Architects Act 1963 [28] S.28(1)(a) Architects Act 1963 [29] S.28(1)(b) Architects Act 1963 [30] S.29 Architects Act 1963 [31] S.28(1)(a) Architects Act 1963 [32] S.28(1)(b) Architects Act 1963 [33] Articles 132(3) and 160(2) Federal Constitution of Malaysia 1957 [34] Article 132 Federal Constitution of Malaysia 1957 [35] <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civil_service_in_Malaysia> [36] S.3(2) Architects Act 1963 [37] <https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2014/04/12/high-court-public-servants-dont-have-immunity-from-lawsuits/> [38] S.15A(2)(a) Architects Act 1963 [39] S.15A(2)(b) Architects Act 1963 [40] S.15A(2)(c) Architects Act 1963 [41] S.15A(2)(d) Architects Act 1963 [42] S.15A(2)(e) Architects Act 1963 [43] S.15A(2)(f) Architects Act 1963 [44] S.15A(2)(g) Architects Act 1963 [45] S.15A(2)(h) Architects Act 1963 [46] S.15A(2)(i) Architects Act 1963 [47] S.15A(2)(j) Architects Act 1963 [48] S.15A(2)(k) Architects Act 1963 [49] S.15A(2)(l) Architects Act 1963 [50] S.15A(2)(m) Architects Act 1963 [51] S.15A(2)(n) Architects Act 1963 [52] S.15A(2)(o) Architects Act 1963 [53] S.15A(2)(p) Architects Act 1963 Food for thought…

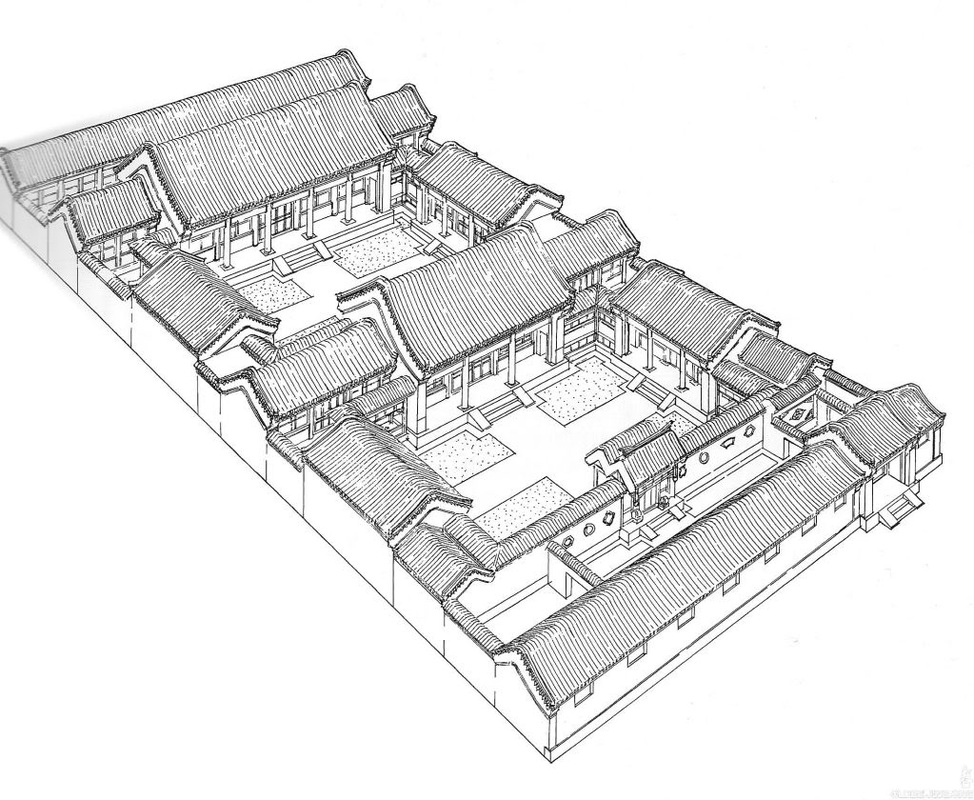

A 1988 amendment to Article 121(1) of the Federal Constitution to remove judicial power from judges[1] did not have the desired effect, Chief Justice Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat said.[2] Constitution must be interpreted in light of its historical and philosophical context, underlying fundamental principles[3]; as in the Westminster’s model, a separation of power among the ‘branches of government’[4]; inherent within, the judiciary role as the ultimate-arbiter corollary to the ‘rules of law’[5]; in no-way inimical to democratic government[6]; but also to interpret statutes[7], as on par with the ‘sovereignty of Parliament’[8]; thus this ‘basic structure’ cannot be abrogated or removed by a constitutional amendment[9]; thus a feature intrinsic to the constitution itself as the supreme-law[10]; vesting upon the judicial power to review against unconstitutional legislation[11], whether or not it is expressly stated[12]; bringing about the significance that judicial-power cannot be removed from civil-courts[13]. Any other courts, i.e. the Syariah Courts, a creature of State Legislative creation, cannot be vested with judicial power as it is unequal to the ‘superior court’ in accordance to the constitutional provisions[14]; repugnant even if the Parliament attempt to amend the constitution to give power to the Syariah Courts[15]. ---------------------------------------------- [1] <https://m.aliran.com/towering-msians/mahathirs-1988-showdown-with-salleh-abas/> [2] <https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2021/01/15/judicial-power-still-with-courts-despite-1988-constitution-amendment-says-cj/> [3] Canadian Supreme Court on Reference re Senate Reform 2014 SCC 32 [4] Mohd Faizal bin Sabtu v Public Prosecutor [2012] SGHC 163 [5] Pengarah Tanah dan Galian WP v Sri Lempah Enterprise [1979] 1 MLJ 135; and R(Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the EU [2017] UKSC 5 [6] Canadian Supreme Court on Reference re Secession of Quebec(supra) [7] R(application of Jackson and Ors) v Attorney General [2005] UKHL 56 [8] Tan Seet Eng v Attorney General & Ors [2015] SGCA 59 [9] Kesavananda Bharti v State of Kerela AIR 1973 SC 1461 [10] Art.4 Singapore Constitution; Attorney General v Taylor [2017] NZ CA 215; Semenyih Jaya v Pentadbir Tanah Hulu Langat [2017] 3 MLJ 36: judicial power vested in the High Courts by virtue of Art.121(1) Malaysian Constitution [11] Lim Kit Siang v Dato Seri Dr Mahathir Mohd [1987] 1 MLJ 383 [12] Hinds v The Queen [1997] AC 195 [13] Public Prosecutor v Dato Yap Peng [1987] 2 MLJ 311 [14] Art 121 Malaysia Constitution [15] Abdul Kahar b. Ahmad v Kerajaan Malaysia and Ors [2008] 2 MLJ 617: purport of Art121(1A); Dalip Kaur v Pegawai Polis Bukit Mertajam Anor [1992] 1 MLJ 1 The Chinese courtyard house is also known as the SiHeYuan house 四合院 or the combination of four courts, forming a center plaza. A basic SiHeYuan house is considered a module capable to be duplicated and expanded when desired. There are many rules governing the design of the SiHeYuan house. These rules are based on the principles of FengShui. There are basically 3 sections of a single module.

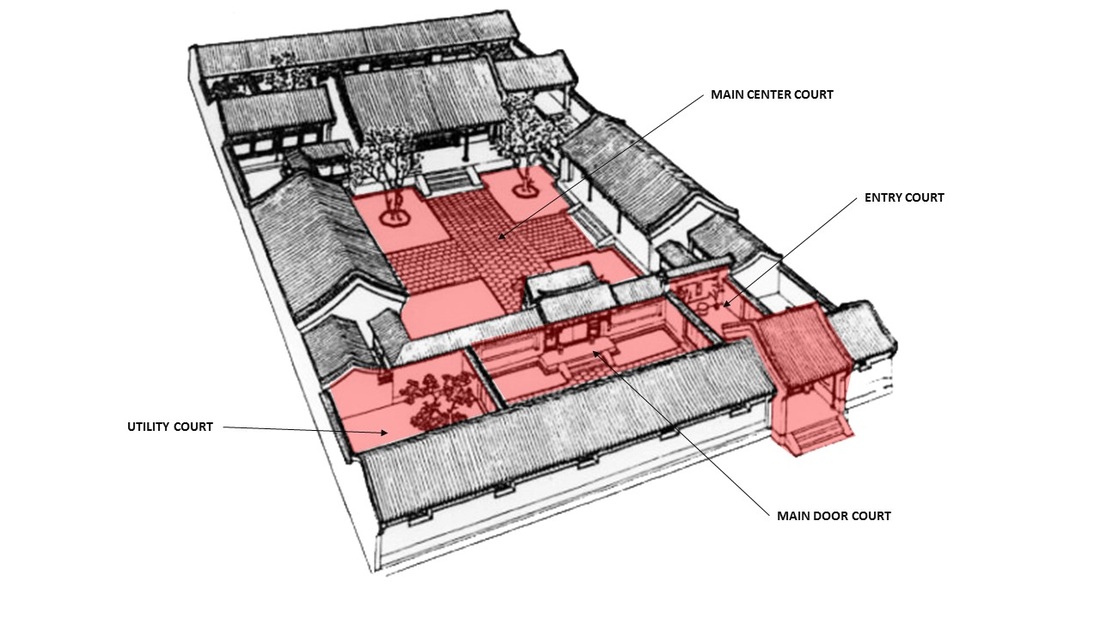

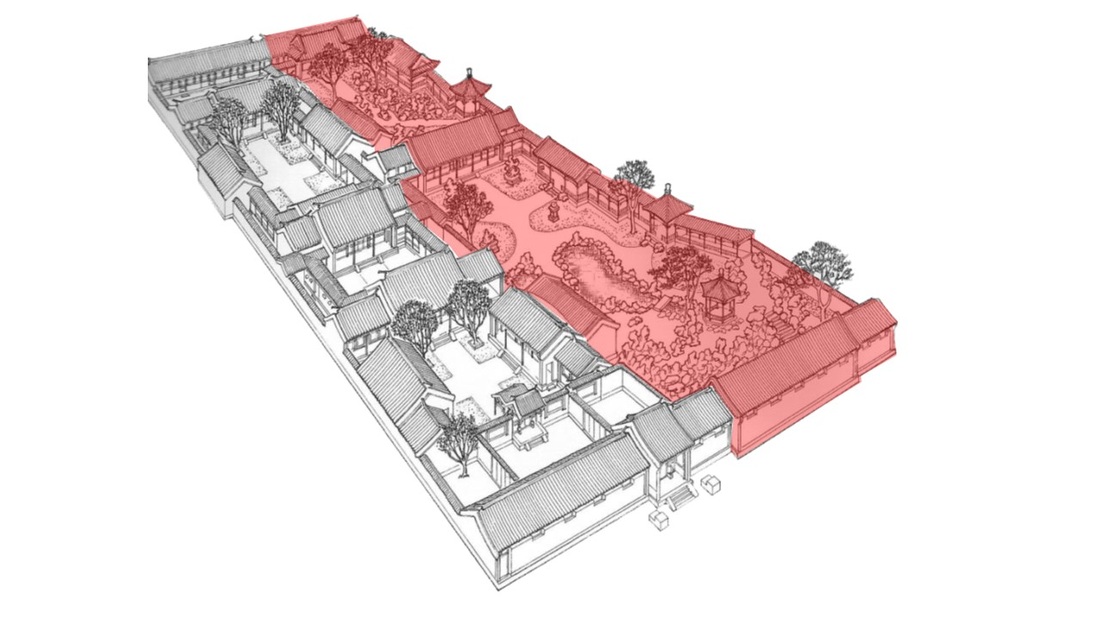

The frontal portion comprises of the "Main Gate" and a terrace of worker's quarters to the left of the "Main Gate" and the horseman station to the left. Many people assumed that the "Main Gate" as the Main Door but this is not the case. The inhabitant takes the street as public spaces and high walls are desirous to conceal the private spaces within. So the worker's quarters, horseman station and the main gates are barricading the street front. The main gate is always located to the right side, looking from the street. It is in the location of Xun 巽 within the Green Dragon Embrace 青龍. The Center Portion is the house proper. Aligned to the center is the Main Door. This Main Door opens up to a huge center court. Only VIP and family members can come in from the Main Door to the house proper. Only males can be seen walking pass the center court. Females are not allowed to use the center court. They can only pass through the terraces that link to the western wing also known as the White Tiger Embrace 白虎. Only on special occasions like festivity, marriages and ushering newborns, females are allowed to be seen in the center court. The western wing is the living abode for the females. The opposite is called the eastern wing also known as the Green Dragon Embrace 青龍. The eastern wing is the living abode for the males. Contrary to FengShui principles that the Green Dragon Embrace 青龍 must be higher than White Tiger Embrace 白虎, the female quarters are higher than the male quarters for practical reason - allowing the female to see and not to be seen from the ground level. Aligned to the center and opposite of the Main Door, sitting north facing south is the Main Living Hall where official receptions are held. There is no TV room but a large hall comprising of rows of seat with the main feature wall usually heavily decorated with altar and calligraphy. The master room is usually located to the back of the Living Hall. Usually the owner will plant 2 trees at the front of the living hall within the compound of the center court. Whenever the tree wither, it signify bad omens. If it is on the left, it affects the male descendants otherwise if it is on the right, it affects the female descendants. The last portion of the house comprising the kitchen, toilets and the back of house. It is detached away from the house proper through a court of utilitarian in nature. There is also a back door only serves as the entrance for the female members of the family and as the only mean to allow the disposal of "night soil" or sewer. Every sections of the SiHeYuan is comprising a number of buildings complete with its 4 walls and a roof above. So technically SiHeYuan is a compound with many individual houses. The courts are open to sunshine and rain water. There is a complete water reticulation system within the SiHeYuan where waters are designed to flow according to a certain direction in accordance to the FengShui principle. Nothing is rarely left for chances. When the family grows, the extended family require extended place to live. The same module was duplicated to the back, again with a second center court complete with its own left and right wing living quarters with its secondary main hall, yet the secondary module also share the same kitchen. As the family prosper, they may require their very own Chinese garden. They will not turn their main court into a Chinese garden and instead, they will purchase the neighboring lot and be expended into a standalone Chinese garden with internal access ways. So, technically the SiHeYuan remains intact and whatsoever add-ons are a matter of "plug and play".

|

I am sharing these information with a caveat that these information is for educational purpose only and shall not be taken as an advice be it legal or otherwise. You should seek proper advice to your case with the relevant professionals. The author cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information so provided here.

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

- Home

- About

-

Practice

-

DYA + C

-

Consultant

-

Educator

- Author I am...

- Speaking Engagement >

- Attempting Law School

- Journey in USM(Arch) >

- Discourse in Studio 6 >

-

d:KON 4

>

- Actors >

-

Acts

>

- Portraiture

- A Slice of Space Time

- Box of Installation of Lights

- Radio Misreading

- Grid of Destinies

- Shelter

- Anatomy of Pain

- Tensigrity of Ego

- Of Prisons and Walls

- Forest of Nails

- Curtain of Fears

- Dissolution of the Ego

- If it's Ain't Broken it's Ain't Worth Mending

- Flight of Freedom

- Cross of Complexity and Contradiction

- interrogation

- Stage >

- Play

- Approach

- Galleria >

- External Critique >

- Philosophy

- Codes Regulations & Standards >

- Photo Essays

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed